Abstract

Human experience intertwines continuity, the seamless flow of events, with segmentation, the spontaneous partitioning of experience into discrete units. Despite their cognitive significance, it is unclear whether these processes operate independently or share a common mechanism. Here we explored this question by examining the link between serial dependence (SD)—the tendency to align perceptions with prior decisions—and the impact of event boundaries, prompted by contextual shifts, on memory. Considering a Bayesian perspective that associates SD with predictions, and segmentation with prediction errors, a common mechanism may govern both processes. Across three experiments (N = 816), we tested how contextual changes affect SD and segmentation-related memory effects. The results indicate that both processes are context-sensitive. Contextual boundaries can reduce SD even in the absence of sensory change, and boundaries modulate memory in ways consistent with event segmentation. Yet, across experiments we observed dissociable patterns of boundary effects on SD and memory, which are slightly more consistent with distinct contextual influences on perception and memory than with a single unified predictive system. Boundary effects on SD and memory did not covary across participants, but given the low within-participant reliability of these measures, this absence of correlation cannot be taken as strong evidence for independence. Overall, our findings show that both SD and memory are shaped by context, but clarifying whether they reflect a shared or partly distinct mechanism will require further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The subjective sense of continuity and the spontaneous segmentation of our daily experience into episodic events are deeply ingrained in natural human experience. Take, for instance, the act of walking from your home to your office. Although the sensory input swiftly changes as we walk, we don’t perceive each movement of passing pedestrians as a distinct event. Instead, we intuitively sense the flow of information as part of a broader, continuous experience. Simultaneously, this experience would automatically be segmented if we unexpectedly met a friend or transitioned from walking to running due to realizing we are running late for a meeting. Without deliberate intention, processes that uphold the subjective sense of continuity and the segmentation of our experience into discrete units play a crucial role in shaping our everyday experiences.

What is the relationship between continuity and segmentation? Although they seem highly related, segmentation is primarily studied under the umbrella of high-level episodic memory encoding1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, and continuity is typically indexed by the apparent smoothing of rapid, low-level perceptual inputs9,10,11,12,13,14, so the intricate interplay between these concepts remains largely unexplored. One possibility is that continuity and segmentation are two sides of the same process, leading to a ‘two-ends’ prediction where one aspect dominates the other in different circumstances. An alternative possibility is that continuity and segmentation are governed by distinct processes. According to this alternative perspective, continuity and segmentation may coexist at different levels of processing. For example, continuity may be the faculty through which moment-to-moment low-level sensory changes are smoothed, and segmentation may take place independently at the conceptual level, leading to the organization of long-term memory. If this alternative is true, individuals may subjectively perceive their experiences as both continuous and segmented. The primary aim of the current research is to empirically evaluate these divergent predictions.

From a Bayesian standpoint, continuity and segmentation may both be steered by a shared contextual mechanism. Contextual similarity, which facilitates predictions from prior to current events, potentially sustains continuity (for example, perceiving one’s consecutive, predictable steps as a continuous ‘walk’), and contextual change, which is often accompanied by prediction failure (for example, unexpectedly meeting a friend), facilitates segmentation.

Indeed, a large body of research demonstrates that context plays a role in the segmentation of continuous experience into discrete events (that is, ‘event segmentation’15). Studies show that ‘event boundaries’ emerge at points of contextual change3, surprise16 or prediction failure17,18, parsing experience into separate events on either side of the boundary. Event segmentation theory postulates that the brain forms a stable representation of the world in the form of an ‘event model’, which resets and is updated at moments of meaningful change19,20. Event boundaries have been shown to shape the organization and representation of perceptual experiences, and subsequently, their long-term memory21,22. Boundaries and their influence on memory have been observed in paradigms that range from naturalistic scene changes23 through action-related changes24 to specific changes in a context’s perceptual features. For instance, associative binding between an item and its context is enhanced for elements occurring at event boundaries following a change in the context’s attributes (for example, colour), and memory for the order of elements is better for items presented within the same event than for items presented straddling an event boundary1,3,4,6.

It is worth noting that despite the extensive literature on context and segmentation, the question of what is the minimal change that elicits segmentation25 and whether the strength of a boundary modulates its exerted effects on memory has yet to be fully addressed18,26. Stronger boundaries may modulate long-term memory more strongly than weaker boundaries, but alternatively, boundaries may exhibit an all-or-none characteristic, by which a contextual change will elicit the same degree of segmentation, regardless of the change’s magnitude. Additionally, whether sensory change is a prerequisite for the contextual change to trigger segmentation has not been fully addressed. Context changes and sensory changes are often intertwined in the segmentation literature, as context is often defined by a sensory feature and context change manipulated by changes in that sensory feature4,5. Although sensory changes can signal the beginning of a new event, there are scenarios in which it is the lack of sensory change that is used to infer a transition to a new event. For example, when trying to start your car, it is a lack of change that makes you realize something unplanned is happening and that a potential new event of ‘how do I get to work’ is beginning. Low-level changes driven by sensory changes and high-level changes driven by expectations are often confounded in the literature, primarily because learning sensory sequences inherently aids expectation forming27. Within the scope of our goal to learn how context influences segmentation and continuity, we also addressed these two open questions and investigated the role that boundary strength and sensory change play not only in triggering event boundaries but also in maintaining continuity.

The role that context plays in sustaining continuity has not been directly explored. In the past decade, a rapidly growing body of literature has contributed to our understanding of continuity-sustaining processes through the lens of the ‘serial dependence’ (SD) phenomenon. SD refers to the bias of current perceptual decisions towards preceding ones13. To reiterate the walk-to-work example above, every step we perceive is predicted by and biased towards the previously taken step. The pioneering work on SD found that in a randomized line orientation task13, participants’ perceptual judgements are serially dependent, in the sense that judgements are consistently biased towards the preceding percept. Since then, SD has been observed in multiple perceptual domains28,29,30,31 and has more generally been suggested to sustain continuity via linking current and prior inputs across multiple features of experience32,33,34. As would be expected by Bayesian interpretations of SD35,36, this bias towards prior inputs links adjacent events together, giving rise to a continuous experience.

While SD as a continuity-related phenomenon is well established, whether and how it is modulated by contextual changes remains an open question. A preliminary report hints that context change diminishes SD37, and a few studies show that reduced similarity between consecutive trials, in both task-relevant and task-irrelevant features, scales down SD14,38. For example, a change in the background colour of a moving-dot pattern between trials decreases SD in orientation judgements38, implying that continuity along one dimension (for example, orientation) is most strongly sustained between consecutive inputs when these inputs are similar across other dimensions as well (for example, colour). This finding can be interpreted as initial evidence for the potential role context may play in SD. Additionally, and in line with this work, a recent study found SD in how we perceive a face that gradually changes from young to old and suggested that while daily scenarios are rapidly changing at fine-grained timescales, they nonetheless maintain global-level stability over the course of longer timescales (such as the face’s global configuration). The fact that the broader perceptual ‘context’ remains constant is suggested to promote SD, smoothing moment-to-moment changes12. In that sense, the inherent bias towards prior inputs should be facilitated within a stable global context and diminish when the context is changing. The current study tested this prediction.

SD has primarily been explored within the domain of perceptual decision-making using randomly ordered low-level stimuli such as line orientations or moving dots, and in sub-second stimulus presentation timescales. Event segmentation, however, has often been examined in paradigms where meaningful stimuli (for example, objects or faces) are organized in a schematic or episodic structure, in timescales of seconds to minutes. As outlined above, theoretical accounts link both SD and event segmentation to prediction and prediction errors. So while it is plausible that they could be two sides of a shared process, a clear link has yet to be drawn between them. It is unknown whether an increase in one is coupled with a decrease in the other, and whether SD and memory-driven event segmentation react to similar contextual changes.

Here we optimized a paradigm that evokes both SD and segmentation-related memory effects within unified settings. Memorable and meaningful stimuli (that is, objects) were presented to participants in different orientations, and the participants were asked to perform an object orientation task as well as two memory tasks. This set-up enabled the integration of orientation judgements through which SD was assessed, with memory measures indicative of the downstream effects of segmentation. Across three studies, we manipulated context in various ways to probe the direct link between event segmentation in memory and SD. If a shared contextual mechanism underpins continuity and segmentation, alterations promoting segmentation will concomitantly diminish SD. Conversely, independent effects of contextual changes on segmentation and continuity will suggest disparate underlying processes for these phenomena.

In brief, our results suggest that response-related SD is attenuated at contextual boundaries, even when those boundaries involve no sensory change, demonstrating that this continuity-preserving bias can be flexibly modulated by conceptual event structure. At the same time, SD and segmentation-related memory effects were not significantly correlated across participants. Yet given the low reliability of these measures within participants, we view this null relationship as inconclusive rather than as evidence that they are governed by distinct mechanisms.

Results

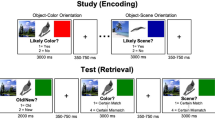

To examine whether continuity and segmentation are governed by shared or dissociable mechanisms, we conducted three experiments using a unified behavioural paradigm (Fig. 1). Participants viewed sequences of objects framed by coloured circles while performing an orientation discrimination task designed to elicit SD, followed by associative and temporal order memory tasks indexing event segmentation. This paradigm allowed us to examine SD and associative memory at boundary and non-boundary items as well as temporal order memory for item pairs that did or did not span a boundary (Experiment 1). In addition to maintaining the boundary/non-boundary distinction across all experiments, we manipulated the characteristics of contextual boundaries by varying their perceptual strength (Experiment 2) and by decoupling them from sensory change (Experiment 3), thus testing how different types of contextual shifts modulate SD and segmentation in memory. With this approach we could assess both processes in parallel, using identical stimuli, and directly compare their sensitivity to various shared contextual cues (Fig. 1).

a, General paradigm of Experiment 1. Tilted images appeared on-screen for 2 s. After a 500-ms delay, the participants were asked to adjust an orientation bar, using their mouse, to fit the preceding object’s orientation. Each block consisted of six events and a total of 36 images, each surrounded by a coloured circle frame. After the presentation of all images in the block, the participants completed two memory tasks. First, the associative memory task tested object–circle-colour memory at either boundary items (the first item in each event) or non-boundary items (the fourth item in each event). Second, the temporal order memory task examined temporal order memory between two images that either belonged to the same event (‘within event’: the third and sixth items in each event) or belonged to different events (‘across boundary’: the fifth item in an event and the second item in the next event). b, Experiment 2. The design was similar to Experiment 1, but the boundaries between events were either weak (that is, an only-shade change from the preceding event) or strong (a change in both colour and shade from the preceding event). Each block consisted of four events and a total of 24 circled images c, Experiment 3. As shown at the top, the participants learned and practiced six event sequences, cued with an associated name and an image (the images depicted in the figure were created by the authors and closely resemble the images used in the experiment). A blocked sequence example is shown at the bottom, depicting the critical boundary conditions: first, a ‘no-change’ boundary, in which the event changes, but the circle’s colour remains the same; and second, a ‘change’ boundary, in which the event boundary is accompanied by a circle colour change. Each block consisted of six events and a total of 36 circled images.

Reduction of SD at contextual event boundaries

Our central hypothesis was that contextual boundaries disrupt perceptual continuity. We therefore examined whether SD, the bias of current perceptual judgements towards previous events, was diminished at points of contextual change. As a first step, we verified that SD reliably emerged in all three experiments by fitting for each experiment a first derivative of Gaussian (DoG) model to the data. This model is often used to characterize SD38,39 and was applied here to orientation-related SD (that is, the bias towards the prior stimulus orientation) as well as to response-related SD (that is, the bias towards the prior response). Since the response in each trial corresponds to that trial’s stimulus orientation, these two biases are highly correlated40. Nevertheless, evidence shows that these two forms of bias can sometimes operate in opposite directions39, and we therefore opted to examine both in our experiments.

SD amplitude

For both orientation-related SD and response-related SD, we computed the DoG amplitude, a measure that captures the bias observed at each specific orientation. This was done by aggregating all data points from all participants (Methods). This analysis revealed significant orientation-related and response-related SD in all experiments (orientation: Experiment 1: amp. = 1.05°, Experiment 2: amp. = 1.12°, Experiment 3: amp. = 0.78°; response: Experiment 1: amp. = 1.63°, Experiment 2: amp. = 1.83°, Experiment 3: amp. = 1.21°; P < 0.001 for all amplitudes in shuffling permutation tests controlling for edge effects; Methods). SD peaked at ~±25° relative to the prior stimulus/prior response (Fig. 2a,b), consistent with previous work13,38.

a,b, The bias towards previous relative orientation (a) and towards previous relative response (b) collapsed across all three experiments. The colours denote participants. The small graphs on the right depict the smoothed averages. c,d, Mean orientation-related SD amplitude (c) and response-related SD amplitude (d) of boundary (blue) versus non-boundary (orange) items computed when aggregating data from all experiments. The light grey histograms denote the distribution of gaps between boundary amplitudes and non-boundary amplitudes in label permutation tests. The dark grey lines denote the data’s observed boundary–non-boundary gap. Label permutation tests were used to assess statistical significance. The P values reflect the proportion of shuffled boundary–non-boundary amplitude differences that exceeded the observed difference. The right-side panels depict amplitudes and label-permutation results separately for each experiment. Though significance varies across experiments, boundary amplitudes are consistently smaller than non-boundary amplitudes.

Next, to test whether SD was modulated by contextual boundaries, we divided the data in each experiment into boundary and non-boundary items and compared the amplitude computed for boundary items and the amplitude computed for non-boundary items using label permutation tests. In all three experiments, both orientation-related SD amplitudes and response-related SD amplitudes were numerically reduced for boundary items compared with non-boundary items. For orientation-related SD, these results were significant in Experiment 3 (Experiment 1: boundary amp. = 1.07°, non-boundary amp. = 1.32°, P = 0.14; Experiment 2: boundary amp. = 1.12°, non-boundary amp. = 1.22°, P = 0.31; Experiment 3: boundary amp. = 0.62°, non-boundary amp. = 0.93°, P = 0.05; label permutation test), and for response-related SD, the difference in amplitude between boundary and non-boundary items was significant in both Experiments 2 and 3 (Experiment 1: boundary amp. = 1.68°, non-boundary amp. = 1.81°, P = 0.26; Experiment 2: boundary amp. = 1.54°, non-boundary amp. = 1.89°, P = 0.04; Experiment 3: boundary amp. = 1.07°, non-boundary amp. = 1.38°, P = 0.04; label permutation test). Note that for the purpose of this analysis, in Experiments 2 and 3 we collapsed items from different boundary conditions into a unified boundary condition and compared them to the non-boundary condition. Pairwise comparisons between SD amplitudes across specific boundary conditions varying in strength in Experiments 2 and in sensory change in Experiment 3 are reported later in the experiment-specific sections.

Although it was not part of the registered analyses, we conducted a post hoc analysis to increase statistical power by aggregating data across all experiments, motivated by the consistent direction of effects observed across studies. This revealed a significant boundary effect on both orientation-related SD amplitude (boundary amp. = 0.92°, non-boundary amp. = 1.15°, P = 0.02, label permutation test; Fig. 2c) and response-related SD amplitude (boundary amp. = 1.45°, non-boundary amp. = 1.69°, P = 0.01, label permutation test; Fig. 2d). These findings demonstrate that contextual boundaries can reduce the magnitude of SD. While the effect was modest and did not reach significance in one of the experiments, its emergence in two of the three main studies, the pilot (Supplementary Information) and the post hoc aggregated analysis supports its reliability.

Mean SD

An additional approach to measuring the effect of boundaries on SD involves computing the mean bias across orientations or responses separately for each participant and separately for boundary and non-boundary items, followed by within-participant pairwise comparisons to assess statistical significance. Due to averaging over all orientations, this method is not sensitive to the dynamic nature of SD across the range of relative orientations or responses, but it provides a per-participant measure of SD, which can then be correlated with measures of segmentation in memory. Here we found a main effect of boundaries on mean orientation-related SD in Experiment 1 (boundary: mean = 0.01, s.d. = 1.48; non-boundary: mean = 0.19, s.d. = 1.17; t271,2 = 1.77; P = 0.03; Cohen’s d = 0.1; confidence interval (CI), (−0.22, 0.01)) but not in Experiments 2 (F270,2 = 0.23, P = 0.79, Bayes Factor (BF01) = 3.53 × 105) or 3 (F271,1 = 0.09, P = 0.76, BF01 = 10.45). A main effect of boundaries on mean response-related SD did not emerge in any of the experiments (Experiment 1: t271,2 = 0.5, P = 0.3, BF01 = 9.74; Experiment 2: F270,2 = 0.91, P = 0.4, BF01 = 2.87 × 105; Experiment 3: F271,1 = 0.32, P = 0.56, BF01 = 10.13; for BF analysis of null effects across analyses, see Methods). As in SD amplitudes, pairwise comparisons between mean SD across specific boundary conditions varying in strength in Experiment 2 and in sensory change in Experiment 3 are reported further in the experiment-specific sections.

The discrepancy in the results between SD amplitude method and the mean SD method could be due to the increased sensitivity of the amplitude method that taps into the expected pattern of SD across previous relative events. The SD amplitude computation aggregates data across all participants and trials to pinpoint orientation-specific or response-specific changes in SD. Averaging SD across all orientations or responses in the mean SD method eliminates the critical orientation/response-specific dynamics of these biases, which may be crucial for capturing relatively subtle differences between boundary and non-boundary conditions.

Contextual boundaries robustly modulate associative and temporal order memory, reinforcing prior findings

We next verified that contextual boundaries indeed elicited segmentation by testing their influence on memory. On the basis of previous findings4,41, we hypothesized that across experiments, associative memory would be enhanced at boundaries, and temporal order memory would be better for within-event pairs than for across-boundary pairs.

Associative memory

As predicted, memory performance in the associative memory task was robustly influenced by contextual boundaries. A significant effect for boundaries emerged in Experiment 1 (t271,2 = 7.06; P = 1.35 × 10−11; Cohen’s d = 0.51; CI, (0.38, 0.63)) and in Experiment 2 (main effect in three-level analysis of variance (ANOVA), F270,2 = 13.69, P = 2 × 10−5, ηp2 = 0.09; Fig. 3a, left and middle). In Experiment 3, which dissociated boundaries from sensory change (Methods), we did not observe an effect for contextual boundaries (F271,1 = 0.02, P = 0.86, BF01 = 9.66; Fig. 3a, right). Nevertheless, when comparing memory for boundary items that involved sensory change with memory for non-boundary items that lacked sensory change, mirroring the standard boundary/non-boundary comparison in the literature, the hypothesized effect of memory enhancement at boundaries was replicated (change boundary versus no-change non-boundary: t = 4.47, P = 1.11 × 10−5, Cohen’s d = 0.16). The complete experiment-specific results on boundary strength (Experiment 2) and sensory change (Experiment 3) are detailed in their respective Results sections.

a, Associative memory is modulated by contextual boundaries (P = 1.35 × 10−11, left). Strong and weak boundaries have equivalent effects on associative memory (P = 2 × 10−5, middle). Associative memory is influenced by sensory change and not by boundaries (P = 6.96 × 10â»13, right). b, Temporal order memory is modulated by contextual boundaries (P = 1.07 × 10−5, left). Strong and weak boundaries have equivalent effects on temporal order memory (P = 0.001, middle). Temporal order memory is modulated by boundaries but not by sensory change (P = 0.04, right). Boundary and across-boundary conditions are represented in cool shades across experiments. Non-boundary and within-event conditions are represented in warm shades. In each box plot, the horizontal line denotes the median, the dot denotes the mean, the box denotes the 25th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers denote the minimum and maximum. The grey lines denote the ANOVA main effect in Experiment 2. The thick black lines denote the main effects in Experiment 3. The dashed lines denote chance level. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant. Two-sided t-tests were carried out in Experiment 1. N = 272 in each experiment.

As our experiments manipulated objects in various orientations, associative memory could be influenced by object orientation, with more effortful processing of objects tilted to greater extents. We therefore ensured that the observed boundary effects were not driven by chance differences in object orientation in any of the experiments. This was done by testing whether absolute object orientation influenced memory performance. Mixed-effects modelling revealed no reliable effect of orientation on associative memory in any experiment (Experiment 1: t = 1.06, P = 0.28, BF01 = 6.25; Experiment 2: t = −1.29, P = 0.19, BF01 = 51.86; Experiment 3: t = −0.31, P = 0.75, BF01 = 1,333).

Temporal order memory

Temporal order memory was also consistently affected by contextual boundaries: as expected, a main effect for boundaries emerged in all three experiments (Experiment 1: t271,2 = 4.48; P = 1.07 × 10−5; Cohen’s d = 0.27; CI, (0.15, 0.39); Experiment 2: main effect in three-level ANOVA, F270,2 = 6.85, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04; Experiment 3: F271,1 = 4.23, P = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.01; Fig. 3b). Experiment-specific effects of boundary strength (Experiment 2) and sensory change (Experiment 3) are detailed later in the Results.

Participant-level estimates of boundary effects on memory

Another way to assess boundary effects on memory is to compute for each participant their normalized difference between boundary and non-boundary items in each memory task and test whether the distribution of scores is significantly different from zero. This approach is not independent from the group-level boundary/non-boundary comparison described above, but it provides a direct measure of boundary-related memory enhancement per participant per measure (henceforth ‘boundary effect score’), and these boundary effect scores are later used for assessing correlations in boundary effects across measurements.

We found that boundary effect scores in the associative memory task were significant in Experiments 1 and 2 (Experiment 1: mean = 0.03, s.d. = 0.07, t271,1 = 6.04, P = 4.81 × 10−9, Cohen’s d = 0.36; Experiment 2: mean = 0.03, s.d. = 0.13, t271,1 = 3.88, P = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.23). Boundary effect scores did not reach significance in Experiment 3 (mean = −0.01, s.d. = 0.11, t271,1 = −1.69, P = 0.09), probably due to dissociating contextual boundaries from sensory change (see the Results section for Experiment 3). Temporal boundary effect scores were significant in all experiments (Experiment 1: mean = 0.02, s.d. = 0.09, t271,1 = 4.41, P = 4.44 × 10−5, Cohen’s d = 0.25; Experiment 2: mean = 0.01, s.d. = 0.08, t271,1 = 3.16, P = 0.001; Experiment 3: mean = 0.007, s.d. = 0.07, t271,1 = 1.63, P = 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.01).

These findings replicate the established effects of contextual boundaries on memory and confirm that segmentation effects persist despite variable object orientation and despite the presence of an intermediate orientation task.

Contextual boundary effects on SD and memory do not covary

After finding that both SD and segmentation in memory are each influenced by boundaries, we reasoned that if SD and event segmentation in memory share a mechanism, we would find interactions between them. We further postulated that the magnitude of their effects would covary, such that greater reductions in SD would be associated with stronger segmentation-related memory effects. To test these hypotheses, we explored for interactions between SD and memory in our data and tested whether boundary effect scores are correlated across SD and memory measures.

SD amplitude

We first examined whether the difference in SD amplitude between boundary and non-boundary items varied as a function of whether items were correctly remembered in the associative memory task. This was done by splitting the data into four conditions (boundary status × memory accuracy), computing an SD amplitude for each condition and using a label permutation test to assess significance. This analysis revealed no interaction between memory accuracy and contextual boundaries in orientation-related SD amplitude (Experiment 1: P = 0.19; Experiment 2: P = 0.6; Experiment 3: P = 0.08) or in response-related SD amplitude (Experiment 1: P = 0.3; Experiment 2: P = 0.35; Experiment 3: P = 0.5).

Mean SD

A repeated-measures ANOVA (boundary status × memory accuracy) on mean SD showed no significant interactions, either for orientation-related mean SD (Experiment 1: F271,1 = 1.08, P = 0.29, BF01 = 2.29 × 104; Experiment 2: F271,1 = 0.02, P = 0.88, BF01 = 1.95 × 104; Experiment 3: F271,1 = 0.9, P = 0.34, BF01 = 5.03 × 104) or for response-related mean SD (Experiment 1: F271,1 = 0.59, P = 0.44, BF01 = 2.9 × 105; Experiment 2: F271,2 = 0.01, P = 0.9, BF01 = 2.09 × 105; Experiment 3: F271,1 = 1.7, P = 0.19, BF01 = 2.26 × 104). Taken together, we did not find evidence that boundary effects in SD interact with memory performance.

Next, to probe potential links at the individual level, we further computed for each participant an ‘SD boundary effect score’, as the normalized difference in response-related mean SD between boundary and non-boundary items, and correlated it with their ‘associative boundary effect score’ and their ‘temporal boundary effect score’. These correlations were not significant with either memory task (Fig. 4, top and middle rows), except that the correlation between associative boundary effect scores and response-related SD boundary effect scores was significant in Experiment 2. These results do not support a shared contextual mechanism for segmentation and continuity.

Top, correlations between associative memory boundary effects and response-related boundary effects are not reliably significant. Middle, correlations between temporal order memory boundary effects and response-related boundary effects are non-significant across all experiments. Bottom, correlations between temporal order memory boundary effects and associative memory boundary effects are non-significant across all experiments. Correlations are calculated over all data points. Participants with extreme response-SD boundary effects (<−8.5 or >8.5) are excluded from the plots for visualization only. The shaded areas represent s.e.m. across participants. Pearson’s r statistic was calculated. There was no correction for multiple comparisons.

In this analysis, we also explored the relationship between associative boundary effects and temporal boundary effects and found no correlation in all experiments (Fig. 4, bottom row). This raises the possibility that while both have been taken as proxies for event segmentation in the past, associative memory and temporal order memory are modulated by contextual boundaries through distinct mechanisms.

An important caveat regarding the lack of observable correlations between boundary effects across measurements is that this could be due to a lack of within-measure reliability. We therefore ran an exploratory split-half analysis that tested within-participant reliability in boundary effects in each experiment and domain (Supplementary Information section 2, ‘Reliability analyses of boundary effects’). These within-domain correlations, considered collectively, did not provide substantial evidence of reliability, limiting strong conclusions about whether SD and segmentation-related memory effects are driven by dissociable mechanisms.

Specific boundaries analysis

In addition to examining the global effects of contextual boundaries, we conducted an analysis to test whether SD and segmentation-related memory effects covaried across specific contextual transitions. For each participant, we measured associative memory, temporal order memory, mean orientation-related SD and mean response-related SD for each unique boundary transition (for example, dark purple to light purple in Experiment 2) and then averaged these measurements across participants. We also measured the orientation-related SD amplitude and response-related SD amplitude for each specific boundary. Lastly, we tested whether reductions in SD at specific boundaries correlated with enhanced associative memory for items following the same boundaries. This analysis was designed to probe the possibility that the relationship between continuity and segmentation may emerge more clearly at the level of specific transitions, even if not evident in broader condition-level comparisons. If such boundary-specific SD effects reflect meaningful contextual salience, they might co-occur with enhanced segmentation. However, correlations between SD and memory across the different specific boundaries were consistently non-significant (Supplementary Information section 3, ‘Specific-boundaries analysis’).

In summary, we found no evidence that boundary-related changes in SD are coupled with boundary-related changes in memory, either across individuals or across specific boundaries. These findings seem to suggest that while both processes are context-sensitive, SD and event segmentation reflect dissociable mechanisms that take place in parallel.

The effect of contextual boundaries’ strength on SD and memory (Experiment 2)

Experiment 2 tested whether the strength of contextual boundaries influences continuity and segmentation in a binary or gradual manner. This was done by introducing both weak and strong boundaries to the main paradigm (Methods). We hypothesized that stronger boundaries would exert greater effects on both SD and segmentation-related memory effects than weaker boundaries.

SD amplitude

In the analysis of SD amplitude, we found that, contrary to our hypothesis, weak boundaries elicited the lowest SD amplitude. For orientation-related SD, items at weak boundaries had the lowest SD amplitude (amp. = 1.16°) compared with strong (amp. = 1.43°) or non-boundary items (amp. = 1.22°), yet none of the paired comparisons reached significance in label-permutation tests (weak versus strong: P = 0.26; weak versus non-boundary: P = 0.42; strong versus non-boundary: P = 0.24). For response-related SD, amplitude at weak boundaries (amp. = 1.38°) was significantly lower than at strong boundaries (amp. = 1.93°, P = 0.03; label permutation test) and non-boundaries (amp. = 1.89°, P = 0.03; label permutation test). Amplitude at strong boundaries did not significantly differ from that at non-boundaries (P = 0.24).

The surprising finding that weak boundaries elicited the lowest SD amplitude could indicate that in the context of this experiment, weak boundaries disproportionately captured attentional resources, thereby disrupting SD. However, this pattern is not reflected in enhanced associative or temporal order memory at weak boundaries, as seen in the memory results.

Mean SD

Analysis of mean SD using a three-level ANOVA test revealed no significant effects of boundary strength on either orientation-related mean SD (F270,2 = 0.23, P = 0.79, BF01 = 3.61 × 105) or response-related mean SD (F270,2 = 0.91, P = 0.4, BF01 = 2.91 × 105).

Associative memory

In the associative memory task, a significant boundary effect emerged in a three-level ANOVA test (F270,2 = 13.69, P = 2 × 10−5, ηp2 = 0.09; Fig. 3b, middle). Pairwise post hoc comparisons showed that memory performance in both strong (mean = 0.37, s.d. = 0.16) and weak (mean = 0.37, s.d. = 0.16) boundary conditions was significantly higher than in the non-boundary condition (mean = 0.34, s.d. = 0.13; strong boundary versus non-boundary: t271 = 3.63; P = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.22; CI, (0.1, 0.34); weak boundary versus non-boundary: t271 = 4.89; P = 1.72 × 10−5; Cohen’s d = 0.29; CI, (0.17, 0.41); Bonferroni-corrected for multiple comparisons). Critically, memory for the two boundary conditions did not significantly differ (t271,2 = 0.95, P = 0.99, BF01 = 9.37).

Temporal order memory

In the temporal order memory task, a significant boundary effect emerged in a three-level ANOVA test (F270,2 = 6.85, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04; Fig. 3b, middle). Pairwise post hoc comparisons revealed that memory performance in the across-strong-boundary condition (mean = 0.54, s.d. = 0.11) was significantly lower than in the within-event condition (mean = 0.56, s.d. = 0.1; across strong boundary versus within-event: t271 = 3.15; P = 0.001; Cohen’s d = 0.21; CI, (0.09, 0.33)). Memory in the across-weak-boundary condition (mean = 0.55, s.d. = 0.10) was also significantly different from the within-event condition (t271 = 2.2; P = 0.02; Cohen’s d = 0.14; CI, (0.001, 0.03)). There was no significant difference between the across-strong-boundary condition and the across-weak-boundary condition (t271 = 1.15, P = 0.24, BF01 = 7.60). In other words, memory for the within-event condition was significantly better than memory for both the across weak boundary and across-strong-boundary conditions, but the difference between the two boundary conditions was not significant.

Taken together, the findings from both memory tasks support the notion that boundaries influence both associative memory and temporal order memory in a binary manner.

Next, although our group-level analyses did not reveal a correlation between boundary effects on continuity and segmentation, we conducted a planned individual-differences analysis. Specifically, we correlated each participant’s difference in performance between strong and weak boundaries in associative memory and temporal order memory with the corresponding difference in mean orientation-related and response-related SD. If both processes were modulated by a common mechanism, participants showing larger memory enhancements for strong versus weak boundaries should also exhibit larger SD reductions in strong versus weak boundaries. However, no significant correlations emerged. Associative memory did not correlate with either mean orientation-related SD (r = 0.04, P = 0.23, BF01 = 15.84) or mean response-related SD (r = –0.04, P = 0.21, BF01 = 15.34). Similarly, temporal order memory did not correlate with either mean orientation-related SD (r = –0.05, P = 0.19, BF01 = 13.73) or mean response-related SD (r = –0.01, P = 0.43, BF01 = 20.44). Here too, we did not find evidence that boundary strength affects continuity and segmentation through shared processes. However, the lack of within-participant reliability hinders strong interpretations of this null finding.

Contextual boundaries and sensory change are dissociable in eliciting segmentation and disrupting continuity (Experiment 3)

In many experimental paradigms and real-world scenarios, event boundaries are accompanied by changes in low-level sensory features. However, whether the characteristic memory effects are related to sensory change or ‘boundariness’ is unknown. For example, research by Lee and Chen42 showed that internally generated boundaries evoke neural representations similar to boundaries generated by changes in sensory input, and De Soares et al.43 recently showed that the neural representation of boundaries of identical inputs shifts depending on changes in top-down attention. It is therefore possible that conceptual changes are sufficient to constitute contextual boundaries in one’s event model, and that in such cases, segmentation will be instigated even when sensory change is absent. Experiment 3 was designed to dissociate sensory change from contextual boundaries by including boundary items without sensory change and non-boundary items with sensory change. This allowed us to test whether continuity and segmentation effects are driven by contextual structure, sensory change or their combination. Prior to the experimental phase, the participants first completed a learning phase in which they learned event sequences where sensory change and contextual boundaries were dissociated. Some events included a sensory change (for example, alternating frame colours), while others did not; likewise, some transitions between events involved a sensory change, whereas others were marked by a lack of change (Fig. 1c). After learning, the participants underwent a practice phase where they intensively practiced identifying the beginnings of the newly learned events. Only participants who performed above threshold at the practice phase were included in the analyses.

SD amplitude

SD amplitude was analysed by first collapsing the data across sensory change conditions to compare SD amplitudes of boundary as opposed to non-boundary items, and additionally collapsing the data across boundary conditions to compare SD amplitudes of sensory change as opposed to no-sensory-change items.

SD amplitude of boundary items was significantly lower than SD amplitude of non-boundary items, both for orientation-related SD (boundary: 0.62°, non-boundary: 0.93°; P = 0.05, label permutation test) and for response-related SD (boundary: 1.07°, non-boundary: 1.38°; P = 0.04, label permutation test).

SD amplitudes were numerically lower following sensory change items than following no-change items, but these differences did not reach significance in either orientation-related SD (no-sensory-change: 0.70°, sensory change: 0.98°, P = 0.08) or response-related SD (no-sensory-change: 1.15°, sensory change: 1.31°, P = 0.20).

The interaction between boundaries and sensory change in influencing SD amplitudes also did not yield significant results (orientation-related SD: P = 0.13; response-related SD: P = 0.25).

Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that for response-related SD amplitude, a difference between boundary and non-boundary items remained significant even when considering only no-sensory-change items (boundary: 1.21°, non-boundary: 1.68°; P = 0.03, label permutation test). This demonstrates that response-related SD amplitude can be modulated by the existence of conceptual boundaries even in the absence of any sensory change. Additionally, a significant difference in amplitude emerged between sensory change and no-sensory-change conditions, within non-boundary items (change: 1.22°, no change: 1.68°; P = 0.04, label permutation test). Together, these results demonstrate that both contextual boundaries and sensory change can reduce response-related SD.

Mean SD

Next, analysis of mean orientation-related SD revealed no significant boundary effect (F271,1 = 0.09, P = 0.76, BF01 = 10.45) and no significant sensory change effect (F271,1 = 2.95, P = 0.08, BF01 = 3.15). For mean response-related SD, no boundary effect was observed (F271,1 = 0.32, P = 0.56, BF01 = 10.13), but a significant sensory change effect emerged (F271,1 = 5.58, P = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.02) with lower SD for items following sensory change (mean = 0.23, s.d. = 1.21) than for items following no sensory change (mean = 0.47, s.d. = 1.55).

Associative memory

Analysis of the associative memory task did not show a main effect for contextual boundaries (F271,1 = 0.02, P = 0.86, BF01 = 9.66; Fig. 3a, right; as reported above in the contextual boundaries in associative memory section), but a main effect for sensory change emerged (F271,1 = 53.25, P = 6.96 × 10−13, ηp2 = 0.16), with items following sensory change (mean = 0.43, s.d. = 0.23) remembered better than items following no sensory change (mean = 0.40, s.d. = 0.21). Contextual boundaries and sensory change did not interact (F271,1 = 2.39, P = 0.12, BF01 = 1.56 × 103), yet when we compared the change-boundary condition (mean = 0.44, s.d. = 0.24) with the no-change-non-boundary condition (mean = 0.40, s.d. = 0.22) post hoc, the typical boundary effect emerged (change boundary versus no-change non-boundary: t = 4.47, P = 1.11 × 10−5, Cohen’s d = 0.16), in line with findings from prior studies. By dissociating sensory change from contextual boundaries, these results imply that the typical boundary effect on associative memory is primarily driven by the sensory change that boundaries often entail.

Temporal order memory

In the temporal order memory task, a significant boundary effect was observed (F271,1 = 4.23, P = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.01; Fig. 3b, right), with better temporal order memory for within-event than for across-boundary item pairs, as expected. We did not find an effect of sensory change (F271,1 = 0.30, P = 0.58, BF01 = 9.07) or an interaction between contextual boundaries and sensory change (F271,1 = 1.72, P = 0.19, BF01 = 2.57 × 104).

Altogether, the main findings in this experiment reveal a triple dissociation: response-related SD amplitude is modestly influenced by contextual boundaries and to some extent by sensory change; associative memory is shaped selectively by sensory change; and temporal order memory is selectively modulated by contextual boundaries, but not by sensory change.

To ensure the validity of effects observed in the no-sensory-change boundary condition, we conducted a sub-sampling analysis that tested the reliability of the change/no-change manipulation. Unlike traditional boundaries that involve perceptual shifts, here no-sensory-change boundaries depended entirely on participants’ internalized understanding of the contextual structure, established during the learning and practice phases. However, successful identification of such boundaries may have varied across participants, potentially introducing noise into the main analyses. To address this, we restricted the analysis to a subset of participants (N = 112) who demonstrated equivalent sensitivity to sensory-change and no-sensory-change boundaries during the practice phase. This approach allowed us to isolate effects among participants who had reliably learned the event structure, ensuring that any observed differences could not be attributed to variability in boundary detection. The pattern of results in this more rigorously defined sample closely mirrored the full-sample findings in the associative memory and temporal order memory tasks. Nevertheless, with regard to SD amplitudes, two differences from the main results were observed. First, orientation-related SD amplitude reduction at boundaries compared with non-boundaries showed a trend yet did not reach significance. Second, response-related SD amplitude reduction under sensory change compared with no sensory change did reach significance (Supplementary Information section 4, ‘Learning reliability analysis’). With regard to the latter finding, it is possible that limiting our analyses to participants who showed equivalent learning of event conditions enhanced our ability to detect subtle sensory-based changes in response-SD amplitude.

SD and memory performance change over time, but their contextual modulations remain stable and uncorrelated (exploratory analysis)

After demonstrating that context probably influences SD and memory-based segmentation through dissociable mechanisms, we conducted an exploratory analysis to examine whether these effects vary over the course of the experiment, as it remains unclear whether and how each process evolves with time.

To this aim, we fit mixed-effects modelling, predicting mean response-related SD and memory performance from the time-on-task factor (that is, trial number). The results showed that in all experiments both mean response-related SD (Fig. 5a) and memory performance (Fig. 5b,c) changed over time, with increased mean SD and decreased memory performance as the experiment progressed (mean response-related SD: Experiment 1: t = 6.73, P = 1.66 × 10−11; Experiment 2: t = 2.72, P = 0.006; Experiment 3: t = 5.37, P = 7.82 × 10−8; associative memory: Experiment 1: t = 2.09, P = 0.03; Experiment 2: t = 2.02, P = 0.02; Experiment 3: t = 5.37, P = 7.89 × 10−8; temporal order memory: Experiment 1: t = 3.92, P = 8.62 × 10−5; Experiment 2: t = 4.92, P = 8.63 × 10−7; Experiment 3: t = 4.25, P = 2.1 × 10−5). It is worth noting that absolute error in orientation judgements did not decline over time, so these effects cannot be attributed to reduced performance in the orientation task. Most importantly, while SD and memory performance changed over time, their respective boundary effects did not change over time in any of the experiments (mean response-related SD: Experiment 1: P = 0.75; Experiment 2: P = 0.69; Experiment 3: P = 0.33; associative memory: Experiment 1: P = 0.2; Experiment 2: P = 0.52; Experiment 3: P = 0.25; temporal order memory: Experiment 1: P = 0.96; Experiment 2: P = 0.27; Experiment 3: P = 0.66; mixed-effects models). These exploratory results further suggest that while SD and segmentation-related memory effects can emerge in shared settings, these phenomena are not directly linked, and their modulation by context is time-insensitive.

Discussion

The main goals of the current study were to assess whether contextual boundaries modulate SD and to test whether this potential effect is correlated with the established effects of boundaries on memory1,3,4,5. Such a link would have provided evidence for the idea that a common mechanism underlies both continuity and segmentation, positioning them along a single continuum. To address these aims, we developed a paradigm that elicited both SD and event segmentation in memory within a unified setting, allowing us to test how each process is modulated by different contextual manipulations. We found that response-related SD amplitude was reduced at contextual boundaries in two of the three main experiments, in the pilot and in a post hoc aggregated data analysis. Importantly, response-related SD was modulated by contextual boundaries even in the absence of sensory change. We also robustly replicated the anticipated contextual boundary effects on memory. Lastly, although context change modulated both SD amplitude and memory, the two measures exhibited different patterns of sensitivity to boundary strength and manipulation of sensory change, which hints at distinct mechanisms underlying continuity and segmentation. Boundary-related changes in SD and memory also did not covary across trials or participants, but this may be due to the low within-participant reliability of these measures. Together, these findings indicate that response-related SD and segmentation-related memory are both sensitive to contextual structure, but our data do not allow strong conclusions about whether they arise from a shared mechanism or distinct ones. We illuminate several key new findings in the event segmentation domain. Experiment 2 revealed that boundary strength influenced both associative memory and temporal order memory in a binary rather than gradual fashion. In Experiment 3, sensory change selectively affected associative memory, while temporal order memory was driven by contextual boundaries even in the absence of sensory change.

Modulation of SD by event boundaries

Our results demonstrate that SD can be attenuated at event boundaries. SD has been shown to be influenced by various factors, such as the similarity between current and prior sensory inputs14,38, task demands44 or working memory delays45,46, treating SD as a default feature of perceptual processing, operating independently of broader contextual structure. Here we demonstrate that response-related SD can be selectively attenuated at event boundaries, showing that it is not always uniformly applied across all moments in time but can rather be gated by higher-level contextual cues. In contrast, orientation-related SD amplitude was not reliably sensitive to boundaries across the different experiments. These results demonstrate that response-related SD in particular is more cognitively regulated than previously assumed.

Remarkably, in Experiment 3, we found that response-related SD amplitude was attenuated even at purely conceptual boundaries, those defined by learned contextual transitions, in the absence of any sensory change. This finding is surprising given that SD has often been attributed to mechanisms in early visual processing and interpreted as reflecting sensory-level continuity at the lowest levels of processing13,30,47. The finding that learned contextual boundaries without accompanying visual transients can reduce SD suggests that the phenomenon is not confined to early sensory circuits. Rather, it can be dynamically modulated by contextual knowledge, possibly via top-down signals that influence perceptual integration in support of event-structure continuity. In parallel, we have also observed that SD is modulated by sensory change, independent of boundaries. Together, these findings align with emerging views of SD35 where SD is influenced by top-down factors such as attention and memory but also depends on the visual properties of the stimulus. Our findings therefore resonate with understanding SD as a hybrid phenomenon: it is grounded in perceptual history but is modulated by representations of learned events. In this view, the early sensory bias that drives SD can be reshaped by higher-order representations of structure, such as the boundaries between events.

While our results show that conceptual boundaries can suppress SD, the relationship between perceptual boundary strength and SD modulation appears more complex. In Experiment 2, we unexpectedly found that weak boundaries reduced SD amplitudes more than strong boundaries. This shows that sensory change may interact with other cognitive factors in shaping SD. One possibility is that the presence of varying boundary strengths heightened participants’ sensitivity to subtle contextual shifts, redirecting attention towards change detection at the expense of prior input integration. This interpretation, though speculative, aligns with accounts linking SD to attentional resources13,39 and further suggests that reliance on prior information may be tuned on the basis of perceived contextual volatility.

Although both orientation-related SD and response-related SD are inherently highly correlated40 and both emerged in all three experiments, we found differences between them in the extent to which they were influenced by contextual boundaries. Modulation of response-related SD amplitude appeared in two studies, in the pilot and in post hoc aggregated data analysis. In contrast, orientation-related SD amplitude was not reliably influenced by boundaries. It is possible that orientation-related SD was less sensitive to boundaries because it is primarily modulated by specific stimulus features, whereas response-related SD, which involves other levels of processing (for example, decisional and motor), is sensitive to higher-level context. An additional driver of the different findings between the two may pertain to the relatively long delay periods between stimulus and response, which have been shown in the past to boost response-related SD39.

Contextual boundaries and sensory change have distinct effects on associative memory and temporal order memory

Our experiments replicate the typically found effects of contextual boundaries on associative memory4,41,48 and temporal order memory1,3,4,5,6,18,26,41,48. These traditional effects emerged despite the design incorporating an interleaved orientation task and tilted object presentation, showing that the effect of boundaries on memory is resistant to moment-to-moment perceptual variations and attentional demands. Importantly, beyond replicating previous observations, several new findings emerged.

First, whether boundary strength has a gradual or binary influence on memory has been an open question18. Addressing this question has important implications for models of event cognition. A binary effect would resonate with a threshold-based mechanism for updating event models, while a gradual effect would support a graded integration account of contextual information. Experiment 2 revealed that for both associative memory and temporal order memory, strong and weak contextual boundaries had equivalent significant effects on memory performance, indicating that it is the presence of a boundary that drives the effect on memory, rather than its strength.

Interestingly, a recent study49 examined the relationship between boundary strength and pattern shifts across the cortical hierarchy during naturalistic movie-viewing. Though not focused on memory, this research reported a graded rather than a binary effect of boundary strength on activation shifts. This graded effect was more pronounced in low-level auditory cortex than in higher-order areas, suggesting that boundary strength may influence neural activity differently across hierarchical levels. As the current study did not measure brain activity, future research will be valuable in linking neural and task-specific behavioural effects of boundary strength within the same experimental paradigm. In this context, we acknowledge the possibility that the weak boundaries in our design may not have been weak enough, and that a more subtle boundary strength manipulation would have yielded a more gradual result.

Second, contextual boundaries are typically thought of as and manipulated through sensory change in the environment, yet one can think of scenarios where a new event begins while the sensory environment remains stable. This can happen, for example, when one’s internal state, motivation or goals have changed26,42. In Experiment 3, sensory change, but not contextual boundaries, had a significant effect on associative memory. This implies that the commonly observed improvement in associative memory at boundaries is driven, at least in part, by sensory change rather than purely by boundaries. It is also possible that within the specific task design, the condition of no-change boundaries seemed counterintuitive to participants and attentionally demanding, leading to diminished associative memory.

Experiment 3 further showed that, contrary to associative memory, temporal order memory was influenced exclusively by contextual boundaries. After learning event structures, knowing that a new event had begun was sufficient to impair temporal order memory of across-boundary pairs. These results are in line with event-boundary accounts that highlight that both changes in internal state and changes in sensory inputs can elicit event boundaries in memory50,51,52.

Associative memory and temporal order memory were both taken as proxies for event segmentation, but our results show that these tasks were influenced by boundaries in distinct ways. Associative memory was more influenced by sensory change, while temporal order memory was solely influenced by contextual boundaries. It is possible that the characteristic effect of boundaries on associative memory is partly accounted for by sensory-change accounts, and that the temporal order memory task is better suited to examining purely boundary-related effects. More broadly, our results highlight the need to dissociate the unique ways by which boundaries shape event models in memory.

No evidence for a shared contextual mechanism modulating SD and memory

We did not observe robust correlations between boundary effects on SD and memory across participants, but given the limited within-participant reliability of these measures, this absence of correlation cannot be taken as strong evidence about dependence or independence. At the same time, the different modulation of SD and memory by boundary strength and sensory change is more consistent with distinct influences than with a single shared contextual mechanism, and we did not find any evidence in favour of a common mechanism. It is tempting to speculate that SD operates primarily at lower levels of the perceptual hierarchy, smoothing minor variations to maintain stable representations, while segmentation is driven by higher-level model updates signalled by meaningful contextual changes. From this perspective, perceptual continuity and event segmentation may reflect distinct but complementary strategies: one minimizes moment-to-moment surprise, and the other enhances the salience and memorability of notable transitions. However, the finding that SD was modulated by conceptual boundaries, even in the absence of sensory change, and that associative memory was strongly influenced by sensory change regardless of boundary presence indicates that neither process is confined to a single level of processing, sensory or conceptual.

A future direction to further assess whether SD and event segmentation in memory rely on shared mechanisms is to test whether they are supported by shared brain activations. While there are several studies showing that hippocampal activity supports segmentation and event representation5,8,53, neuroimaging studies of SD are scarce and primarily point to activity in low-level regions47. The paradigm developed here, which examines both phenomena under the same settings, could be used as a powerful approach to test this question in a well-controlled manner.

The independence we observed between continuity and segmentation effects suggests that the brain flexibly balances these competing demands rather than strictly trading off one against the other. This aligns with recent work showing that cognitive flexibility, the ability to switch between tasks, and cognitive stability, the ability to focus on a current task, are not opposite ends of a single continuum but rather reflect two distinct dimensions, with trade-offs emerging only in contexts that specifically demand one over the other54. Within the current scope, a similar division between segmentation and continuity may serve to maintain perceptual coherence while simultaneously constructing a structured, segmented memory of experience that supports planning, learning and future prediction.

Our findings should be weighed against several key limitations. First, although contextual boundaries reduced SD and modulated associative and temporal order memory, exploratory analysis further indicated that boundary effects on both SD and memory were not reliably detected within participants. This variability, combined with modest effect sizes55, probably obscured any potential links between the two processes, limiting our ability to firmly reach a distinct-mechanisms conclusion. It is also important to note that in the current study, segmentation was measured using a higher-level memory task, while continuity was assessed at a lower level of perception. Thus, the observed independence in their contextual effects may arise, in part, from the different levels at which each process was tested. Future studies designed to assess segmentation through more perceptual tasks (for example, temporal distance judgements) and continuity through higher-level tasks (for example, SD in categorical judgements) may help determine whether the observed dissociation reflects inherent differences between the two processes or arises from differences in how they were assessed.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal that SD can be modulated by contextual boundaries even in the absence of sensory change, and that temporal order memory is modulated by boundaries but not by sensory change, whereas associative memory shows the opposite pattern. Boundary-related changes in SD and memory did not correlate across participants, but given the limited within-participant reliability of these measures, this lack of correlation cannot be taken as strong evidence regarding whether their contextual modulation relies on shared or distinct mechanisms. Taken together, the results indicate that context shapes both the maintenance of perceptual and conceptual stability and the segmentation of experience into discrete, memorable events, while leaving open the question of whether a single mechanism or distinct mechanisms underlie these contextual influences.

Methods

Ethics information

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hebrew University (IRB_2024_056). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants were reimbursed six British pounds per hour for their participation. All experiments were of a within-participant design; therefore, randomization in allocating participants to specific experimental conditions did not apply, yet data collection was blind to within-experiment task conditions.

General experimental scheme

In three experiments, the participants viewed objects in various orientations, each surrounded by a coloured circle frame that served as context for the objects4, and performed an object-orientation task, which classically exhibits SD10,13,56,57. This was followed by two memory tasks: associative memory for the colour of the circle frame that surrounded each object and temporal order memory for pairs of objects. Both memory tasks have been shown to be modulated by boundaries1,4,6,27. In line with these previous studies, we hypothesized that associative memory would be enhanced for boundary items and that temporal order memory would be better for images appearing within an event than for images appearing across events. At the same time, SD was hypothesized to decrease at event boundaries (Design table, Question 1). Experiments 2 and 3 expanded our in-principle investigation of context and were carried out to probe whether different manipulations of contextual boundaries have opposing effects on SD and segmentation (Design table, Questions 2 and 3).

It is important to note that in Pilot Experiment 1 (Supplementary Information section 1) we obtained preliminary evidence that SD co-occurred with boundary-related associative memory effects in a unified setting, but not with temporal order memory effects. This raised the possibility that the object orientation task obscures performance in the temporal order memory task, as focusing on the orientation of the object may have shifted one’s attention towards processing each image’s features at the expense of awareness of the order of images. It is also possible that this was a matter of power. Nevertheless, Pilot Experiment 2 confirmed that boundary-related effects on temporal order memory do emerge in the proposed paradigm when the object orientation task is removed from the design.

All experiments were run online, hosted by Pavlovia (https://pavlovia.org). Participants were recruited and paid via Prolific (www.prolific.com). The participants first signed an online consent form, after which they received task instructions and completed the experiment. The participants were compensated six pounds per hour for participation. The mean age and sex across all participants in all experiments was as follows: Experiment 1: 32.72 (s.d. = 6.89), 155 females; Experiment 2: 31.85 (s.d. = 7.17), 166 females; Experiment 3: 31.45 (s.d. = 7.31), 240 females. Some participants were subsequently excluded for below-threshold performance.

Experiment 1

Participants

Experiment 1 (and all experiments in the study) involved 272 participants, computed on the basis of a power analysis planned to obtain effect sizes of 0.2, with power of 0.95. A balanced gender-inclusion criterion was imposed on data collection. The participants were screened for the following criteria: normal or corrected-to-normal vision, native English speaking, lack of colour blindness, and absence of preceding memory deficits or neurological or mental health compromised conditions. Age was limited to the range of 18–50 years.

Stimuli

Object images

The object images (N = 450) were chosen and adapted from stimuli sets used in previous studies3,58,59,60,61. The objects were screened for having an elongated shape (for example, fork or umbrella as opposed to watermelon), which is needed for performing the object orientation task. The screened objects were greyscale and resized to a 500 × 500 pixel size. To avoid potential memory confounds related to the ability to name the objects, a naming pilot was run (N = 10) in which participants typed the name of each presented object as fast and as accurately as possible. This verified that all objects were easily nameable (mean naming response time (RT), 1.84 s; s.d. = 0.88 s). All objects were accurately named, and no objects had a naming RT more than two standard deviations from the mean naming RT.

Context circle frames

The object images were surrounded by coloured circle frames. Thirty-six images were presented in every block. Each block was divided into six events, with one colour repeating throughout the event, during the presentation of six consecutive images. Thus, six colours were used, randomly ordered within each block. Here and in all experiments, the coloured circle frames were used as the dominant feature defining the context in which images were encoded (Fig. 1a).

Experimental procedure and tasks

Each block in the experiment began with an object presentation stage during which the participants performed the object orientation task.

Object orientation task

In the object orientation task, images were presented one after the other, surrounded by coloured circle frames. Each object was randomly tilted in the range of −45° to 45°, in steps of 5° between optional orientations. The range limits were intended to verify that the images could be correctly identified and could be readily encoded for subsequent memory tasks. Each trial began with the presentation of a tilted object image surrounded by a coloured circle frame. The object was presented for 2 s, and the circle frame surrounding each object remained in its colour on-screen throughout the trial until the beginning of the next trial. After the presentation of the object, a fixation cross was presented for 500 ms. Subsequently, a vertical orientation bar appeared on-screen, and the participants were asked to adjust the bar’s orientation to fit the orientation of the just-presented object using the mouse. After the participants responded (no RT limits), a second fixation cross was presented for 500 ms, and the next trial began. The circle frame remained the same colour for six consecutive images, after which it changed to a different colour (Fig. 1a, top). A total of six colours and 36 object images were presented in each block.

During the object presentation stage, and in parallel with the object orientation task, the participants were explicitly asked to form an association of each object with the colour of the circle frame surrounding it. Additionally, as done in past studies4, the participants were asked to memorize the order of presented objects in the block. To aid associative memory, the participants were encouraged to imagine the object in the colour of its surrounding circle frame. They were also encouraged to think of a potential ‘storyline’ that connected consecutive images, which was expected to aid temporal order memory.

Following each block of the object presentation stage, the two memory tasks took place as follows.

Associative memory task

The associative memory task was a two-alternative forced choice. In each trial, the participants were presented with an object and two coloured circles and were asked to use their mouse to indicate which of the presented coloured circles had surrounded the object during the object presentation stage. One of the coloured circles was always the target, and the lure was chosen from either the preceding or the following event (for example, Fig. 1a, bottom left). Memory was probed for the first and fourth images of each event in the block (aside from the first object presented in each block, which was not probed). First-position items were considered boundary items, as they followed an event boundary, and fourth-position items were considered non-boundary items. In line with previous protocols4, associative memory for objects from the first half of the block was probed before objects from the second half of the block (the items were randomly ordered within their respective block halves). This was designed to control for potential memory confounds resulting from differences in encoding–retrieval temporal distance. The test was self-paced.

Temporal order memory task

In each temporal order memory trial, two objects were presented on-screen, and the participants were asked to indicate which of them was presented first at encoding (Fig. 1a, bottom right). Half the trials probed memory for within-event temporal order (comparing the third and sixth images in each event), and half probed across-event memory for the order of two images appearing across two sides of an event boundary (comparing the fifth image of an event with the second image in the subsequent event). Here too, memory for objects from the first half of the block was probed before objects from the second half of the block (the items were randomly ordered within each half-block range). The test was self-paced. At the end of the experiment, the participants were debriefed to verify that they had answered the question of which object appeared first, to exclude anyone accidentally answering in the opposite manner.

The experiment consisted of 12 blocks, each starting with a block of 36 trials of the object orientation stage, followed by tasks assessing associative memory and temporal order memory of the images appearing in that block.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 tested how boundary strength influences continuity and segmentation, hypothesizing that strong boundaries would lead to stronger segmentation and greater SD reduction than weak boundaries (Design table, Question 2). Whether boundary strength modulates the effect on memory is an open question in itself; therefore, this experiment is important in shedding light on this question, independent of how boundary strength influences SD. We manipulated graded levels of contextual sensory change at boundaries. Experiment 2 was therefore similar to Experiment 1, with a few modifications in the number of events employed in each block and the colours of the circle frames surrounding the object images. Here, 24 object images were presented within each block, divided into four events, each with one of the following coloured circle frames: dark purple, light purple, dark orange or light orange. In this experiment, transitions that entailed only a change in shade were considered weak boundaries, and transitions that contained a change in both colour and shade were considered strong. We avoided colour-change-only transitions.

In each block, the order of colours was counterbalanced from a predetermined pool of alternatives that maintained both weak and strong boundaries within a block. An example colour sequence within a four-colour block (Fig. 1b) could be dark purple, light purple, dark orange, light orange. This sequence includes two weak boundaries (first to second and third to fourth) and one strong boundary (second to third). Equal numbers of strong and weak boundaries were maintained across all blocks. Given the shorter block lengths (the presentation of 24 images instead of 36 images as in Experiment 1), the experiment consisted of 18 blocks, instead of 12 blocks as in Experiment 1. The associative memory task was a four-alternative forced choice, with all possible colours presented on-screen. This change was made to avoid providing hints as to the correct response, given that the colours in this experiment are related to one another, and to enable a more subtle test of whether misses are typically made within the same colour (for example, mistaking a light purple for a dark purple). The temporal order memory task remained identical to that in Experiment 1.

The chosen RGB purple and orange colours were piloted in a study where participants (N = 10) viewed coloured circles in a similar event-based block structure, without object images to attend to, and were asked to press a key as fast and as accurately as possible whenever they identified a colour change. This verified that the sensitivity in identifying the difference between dark and light purple is comparable to the sensitivity in identifying the difference between dark and light orange (dark purple: RGB = (0.0039, −1, 0.0039), light purple: RGB = (0.4, −1, 0.0039), sensitivity = 0.77, hit RT = 500 ms; dark orange: RGB = (1, 0, −1), light orange: RGB = (1, 0.33, −1), sensitivity = 0.75, hit RT = 490 ms). This pilot also verified that weak boundaries are noticeable enough to elicit identification of the colour change, as indicated by participants’ high hit rate in the weak-boundary condition (weak hit, 0.84; t9 = 6.23; P = 1.5 × 10−4; one-sample t-test against 0.5 chance-level performance), and that they are nonetheless less salient than strong boundaries, as indicated by the better strong boundary hit rate (strong hit, 0.93; t9 = 3; P = 0.01; strong–weak two-tailed paired t-test comparison).

Experiment 3

In Experiment 3, we dissociated context changes from sensory changes to test whether segmentation that is elicited by context changes in the absence of sensory changes affects memory and decreases SD (Design table, Question 3).

Here the main procedure was preceded by detailed instructions and guided learning and practice stages. During the instructions, the participants were familiarized with six colour-coded event sequences and were asked to memorize them (Fig. 1c). These were presented alongside a cueing name (for example, the ‘piggy bank’ event cueing the pink event) and for a duration determined by the participant, to guarantee successful familiarization. Some events were constant in their colour, such that all six consecutive trials of the event depicted the same colour for the circle frame (for example, the ‘piggy bank’ event consisted of six pink circle frames). Other events in this paradigm consisted of two colours alternating three times within the event (for example, the ‘parasol’ event consisted of alternating blue and yellow circle frames). Across all events there were a total of six unique circle-frame colours. Critically, some events ended in the colour that another event began with (for example, the ‘parasol’ event ends in light blue, and the ‘butterfly’ event starts with light blue; Fig. 1c, top).