It’s time for another review for books I read this year (previously: 2024, 2022). According to my GoodReads, I read 27 books this year. Here are some highlights:

The Demon-Haunted World

I started the year with Carl Sagan’s The Demon-Haunted World, as some kind of antidote to current / coming events. I last read this in about 2010, and held it in very high regard. I still do, but Carl comes off as a bit of a fuddy duddy at times (especially when talking about “the youth” today / in the 1990s). That’s not to say that he’s wrong about where society has gone (quiet the opposite), but it as a kind of tone. If you’re interested in an introduction to skepticism, I’d probably recommend the Skeptic’s Guide to the Universe.

Pachinko

Next up was Pachinko, which had been on my list for a while but a friend’s recommendation pushed it to the top. The writing is top-notch and the characters (and the hardship the author threw at them) are still with me 11 months later.

That same friend recommend The House in the Cerulean Sea, which I read this year. I also liked it too, but not enough to rush out and read the sequel.

The Mercy of Gods

This is a new series from the authors behind The Expanse, but the setting and tone are completely different. The feelings that have stuck with me the most are the bleakness and how people survive in desperate times. Not the most uplifting stuff, but an enjoyable (or at least entertaining) read. I’m looking forward to reading more in the series when they come out.

Sailing Alone around the World

This book is a gem, and got my only 5-star of the year (aside from a re-read of another 5-star). I’d recommend it to anyone, even if you aren’t into sailing. Slocum tells the story of the first (recorded) single-handed circumnavigation of the world, which he made aboard the Spray starting in 1895. He’s an incredible writer: both in clarity and style. I loved the understated humor sprinkled throughput.

And his descriptions of the people he met along the way was surprisingly not racist, and maybe even progressive for the time. He managed to avoid the “noble savage” trope entirely. And for the most part he avoided casting any non-American / non-Europeans as “savages” of any kind (aside from the indigenous people in Tierra del Fuego who, admittedly, did try to kill him).

This is available on Project Gutenberg. Check it out!

Service Model

A fantastic little story. It took me a little while to realize that it’s actually a (dark) comedy, but once I did I was along for the ride.

I won’t spoil much it but there’s a small part that tech people / computer programmers will find entertaining. A character used the term “bits” in a couple places where I thought they should have used “bytes”. I assumed that the author (Adrian Tchaikovsky) had just made a small mistake, but no: he knew exactly what he was doing.

Nonfiction

A couple of economics books slipped into my non-fiction reading this year. First was The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes by Zachary D. Carter (audiobook). Reading Keynes and commentary on Keynesian economics was a big part of my undergraduate education. Robert Skidelsky’s three-volume John Maynard Keynes is still my high-watermark for biographies.

This book gave a shorter and more modern overview of Keynes, both his life and economics (which really are inseparable).

In a similar vein, I listened to Trade Wars Are Class Wars. I can’t remember now who I got this recommendation from. I don’t remember much of it.

In the “Boating non-fiction” sub-sub-genera, I had two entries (I guess Sailing Alone around the World goes here too, but it’s so good it gets its own section).

- Into the Raging Sea by Rachel Slade: A fascinating look at the disaster that sank the container ship El Faro in the Caribbean (in 2015, so it’s not ancient history!). I won’t spoil anything, but it really is like a slow-motion train wreck. Slade does a great job telling the story.

- Sailing Smart by Buddy Melges and Charles Mason. I’ve been sailing on a Melges boat and I’m from the Midwest (Buddy is from Wisconsin) so this was like catnip to me. This was part auto-biography, part sail-racing tips. The biography part feels like pretty much any biography from a successful person (i.e. selecting on the dependant variable). I’m not a good enough sailor to judge the sail-racing tips. But it was a quick read.

Newsletters

It’s not books, but I did read every edition of a couple newsletters:

- Money Stuff by Matt Levine. And the Money Stuff podcast he hosts (with Katie Greifeld) is consistently a highlight of my week (RIP Friend of the Show Bill Ackman).

- One First by Steve Vladeck. This is useful for keeping up to date with legal news, especially things around the Supreme Court. But even more valuable is Steve’s analysis.

Hodgepodge

A few quick thoughts on a handful of books.

- A Psalm for the Wild Built, by Becky Chambers: The second Becky Chambers book I’ve read. She’s great. The actual story didn’t do much for me, but the interesting characters moving through an interesting world more than made up for that.

- To shape a Dragon’s Breath, by Moniquill Blackgoose (audiobook). I enjoyed it.

- Murderbot (again). I haven’t watched the TV show, but I re-read all the books when I was in a bit of a slump and needed something light. ART and Murderbot are the best.

- The Overstory by Richard Powers. I stopped reading this a few years ago after a certain character had a certain accident that just felt… unearned, about halfway through the book. I probably should have kept reading but couldn’t. Anyway, I picked up the audiobook and finished it off. It is a great book, but parts of it were a slog to get through.

- No Country for Old Men, by Cormac McCarthy. The Blank Check podcast covered the Coen Brothers this year so I picked up No Country. For me it’s not quite at the level of The Road but it’s still great.

- Mythos by Stephen Fry (audiobook). I highly recommend the audiobook for this one, since Stephen Fry narrates it himself. I never took a Greek History / civilization course in college, but this seemed like a really good overview.

- Endymion by Dan Simmons. This was a bit of a letdown after the first two parts of the Hyperion Cantos (which are just masterpieces). Still fun, but I haven’t moved on to the next book yet.

- A Little Hatred by Joe Abercrombie. This was a strangely easy, flowing read about a pretty awful world.

- The Adventures of Amina Al-Sirafi by Shannon Chakraborty. This book ruled. Amina rules.

- Shards of Earth by Adrian Tchaikovsky. Not my favorite Tchaikovsky, but still interesting.

- Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr. This was a re-read for me, after I recommended it to some friends. I felt bad for accidentally recommending a 600 page book (the downside of e-readers: you don’t appreciate how long a book is). I just love the characters, the story, the message, everything.

This post gives detailed background to my PyData Global talk, “GPU-Accelerated Zarr” (slides, video). It deliberately gets into the weeds, but I will try to provide some background for people who are new to Zarr, GPUs, or both.

The first takeaway is that zarr-python natively supports

NVIDIA GPUs. With a one-line zarr.config.enable_gpu() you can configure zarr

to return CuPy arrays, which reside on your GPU:

>>> import zarr

>>> zarr.config.enable_gpu()

>>> z = zarr.open_array("path/to/store.zarr", mode="r")

>>> type(z[:])

cupy.ndarray

The second takeaway, and the main focus of this post, is that that simple one-liner leaves performance on the table. It depends a bit on your workload, but I’d claim that Zarr’s data loading pipeline shouldn’t ever be the bottleneck. Achieving maximum throughput today requires some care to ensure that the system’s resources are used efficiently. I’m hopeful that we can improve the libraries to do the right thing in more situations.

This post pairs nicely with Earthmover’s I/O-Maxing Tensors in the Cloud post, which showed that network and object storage service (e.g. S3) also shouldn’t be a bottleneck in most workloads. Ideally, your actual computation is where the majority of time is spent, and the I/O pipeline just gets out of your way.

Some background

I imagine that some people reading this have experience with Zarr but not GPUs, or vice versa. Feel free to skip the sections you’re familiar with, and meet up with us at the Speed of Light section.

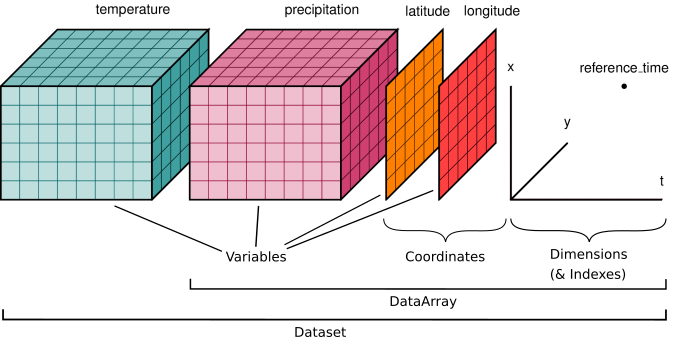

Zarr Background for GPU People

Zarr is many things, but today we’ll focus on Zarr as the storage

format for n-dimensional arrays. Instead of tabular data, which you might store

in a columnar format like Apache Parquet, you’re working with data that fits

things like xarray’s data model: everything is an n-dimensional array with

metadata. For example, 3-d array measuring forecasts for a temperature field

with dimensions (x, y, time).

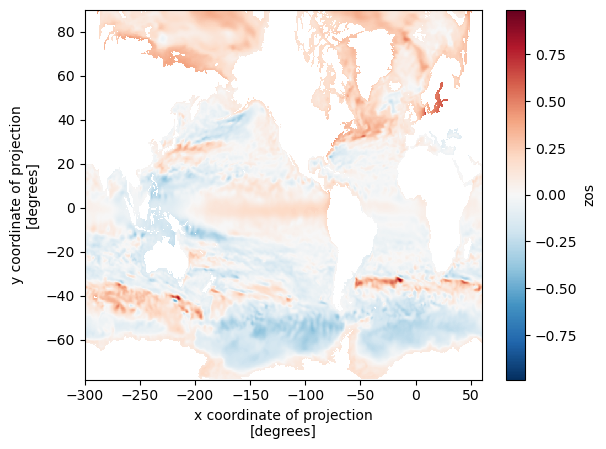

Zarr is commonly used in many domains including microscopy, genomics, remote sensing, and climate / weather modeling. It works well with both local file systems and remote cloud object storage. High-level libraries like xarray can use zarr as a storage format:

# https://tutorial.xarray.dev/intermediate/remote_data/cmip6-cloud.html

>>> ds = xr.open_zarr(

... "gs://cmip6/CMIP6/ScenarioMIP/NOAA-GFDL/...",

... consolidated=True,

... )

>>> zos_2015jan = ds.zos.sel(time="2015-01-16")

>>> zos_2100dec = ds.zos.sel(time="2100-12-16")

>>> sealevelchange = zos_2100dec - zos_2015jan

>>> sealevelchange.plot.imshow()

xarray knows how to translate the high-level slicing like time="2015-01-16" to

the lower level slicing of a Zarr array, and Zarr knows how to translate

positional slices in the large n-dimensional array to files / objects in

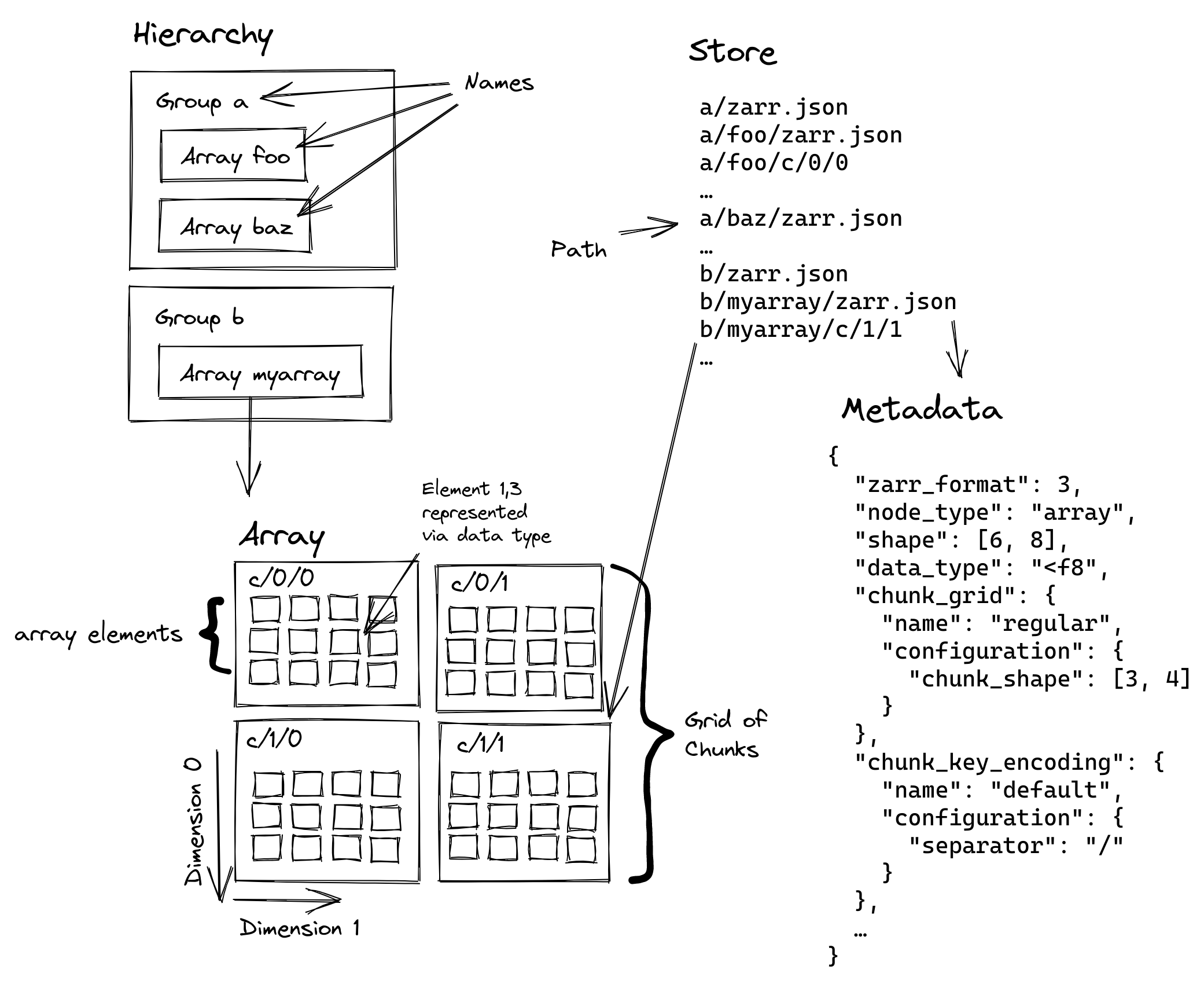

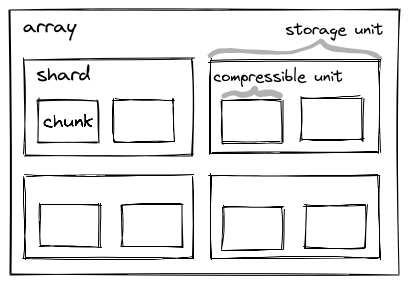

storage. This diagram shows the structure of a Zarr store:

The large logical array is split into one or more chunks along one or more dimensions. The chunks are then compressed and stored to disk, which lowers storage costs and can improve read and write performance (it might be faster to read fewer bytes, even if you have to spend time decompressing them).

Zarr’s sharding codec is especially important for GPUs. This makes it possible to store many chunks in the same file (a file on disk, or an object in object storage). We call the collection of chunks a shard, and the shard is what’s actually written to disk.

Multiple chunks are (independently) compressed, concatenated, and stored into the same file / object. We’ll discuss this more when we talk about performance, but the key thing sharding provides is amortizing some constant costs (opening a file, checking its length, etc.) over many chunks, which can be operated on in parallel (which is great news for GPUs).

For now, just note that we’ll be dealing with various levels of Zarr’s hierarchy:

- Arrays: the logical n-dimensional array

- Shards: the file on disk / object in object storage, which contains many chunks concatenated together

- Chunks: the smallest unit we can read (since it must be decompressed to interpret the bytes correctly)

GPU Background for Zarr People

GPUs are massively parallel processors: they excel when you can apply the same problem to a big batch of data. This works well for video games, ML / AI workloads, and data science / data analysis applications.

(NVIDIA) GPUs execute “kernels”, which are essentially functions that run on GPU data. Today, we won’t be discussing how to author a compute kernel. We’ll be using existing kernels (from libraries like nvcomp, CuPy, and CCCL). Instead, we’ll be worried about higher-level things like memory allocations, data movement, and concurrency

Many (though not all) GPU architectures have dedicated GPU memory. This is separate from the regular main memory of your machine (you’ll hear the term “device” to refer to GPUs, and “host” to refer to the host operating system / machine, where your program is running).

While device memory tends to be relatively fast compared to host memory (for example, it might have >3.3 TB/s from the GPU’s memory to its compute cores), it’s moving data between host and device memory is relatively slow (perhaps just 128 GB/s over PCIe). It also tends to be relatively small (an NVIDIA H100 has 80-94GB of GPU memory; newer generations have more, but still GPU memory is precious when processing large datasets). All this means we need to be careful with memory, both how we allocate and deallocate memory and how we move data between the host and device.

In GPU programming, keeping the GPU busy is necessary (but not sufficient!) to achieve good performance. We’ll use GPU utilization, the percent of time (over some window) when the GPU was busy executing some kernel, as a rough measure of how well we’re doing.

One way to achieve high GPU utilization is to queue up work for the GPU to do. The GPU is a device, a coprocessor, onto which your host program offloads work. As much as possible, we’ll have our Python program just do orchestration, leaving the heavy computation to the GPU. Doing this well requires your host program to not slow down the (very fast) GPU.

In some sense, you want your Python program to be “ahead” of the GPU. If you wait to submit your next computation until some data is ready on the GPU, or some previous computation is completed, you’ll inevitably have some time gap when your GPU is idle. Sometimes this is inevitable, but with a bit of care we’ll be able to make our Zarr example perform well.

My Cloud Native Geospatial Conference post touched on this under Pipelining. This program waits to schedule the computation until the CPU is done reading the data, and so doesn’t achieve high throughput:

This second program queues up plenty of work to do, and so achieves higher throughput:

For this example, we’ll use a single threaded program with multiple CUDA Streams to achieve good pipelining. CUDA streams are a way to express a sequence (a stream, if you will) of computations that must happen in order. But, crucially, you can have multiple streams active at the same time. This is nice because it frees you from having to worry too much about exactly how to schedule work on the GPU. For example, one stream of computation might heavily use the memory subsystem (to transfer data from the host to device, for example) while another stream might be using the compute cores. But you don’t have to worry about timing things so that the memory-intensive operation runs at the same time as the compute-intensive operation.

In pseudocode:

a0 = read_chunk("path/to/a", stream=stream_a)

b0 = read_chunk("path/to/b", stream=stream_b)

a1 = transform(a0, stream=stream_a)

b1 = transform(b0, stream=stream_b)

read_chunk might exercise the memory system to transfer data from the host to

the device, while transform might really hammer the compute cores.

All you need to do is “just” correctly express the relationships between the different parts of your computation (not always easy!). The GPU will take care of running things concurrently where possible.

One subtle point here: these APIs are typically non-blocking in your host

Python (or C/C++/whatever) program. read_chunk makes some CUDA API calls

internally to kick off the host to device transfer, but it doesn’t wait for that

transfer to complete. This is good, since we want our host program to be well

ahead of the GPU; we want to go to the next line and feed the GPU more work to

do.

If we actually poked the memory address where the data’s supposed to be it might

be junk. We just don’t know. If we really need to wait for some data /

computation to be completed, we can call stream.synchronize(), which forces

the host program to wait until all the computations on that stream are done.

But ideally, you don’t need that. For the typical case of launching some

CUDA kernel some some data, synchronization is unnecessary. You only need

to ensure that the computation happens on the same CUDA stream as the data

loading (like in our pseudocode example, launching each transform on

the appropriate stream), and you’re good to go.

CUDA streams do take some getting used to. You can make analogies to thread programming and to async / await, but that only gets you so far. At the end of the day they’re an extremely useful tool to have in your toolkit.

Speed of Light

When analyzing performance, it can be helpful to perform a simple “speed-of-light” analysis: given the constraints of my system, what performance (throughput, latency, whatever metric you care about) should I expect to achieve? This can combine abstract things (like a performance model for how your system operates) with practical things (what’s the sequential read throughput of my disk? What’s the clock cycle of my CPU?).

Many Zarr workloads involve (at least) three stages:

-

Reading bytes from storage (local disk or remote object storage). Your disk (for local storage) or NIC / remote storage service (for remote storage) has some throughput, which you should aim to saturate. Which bytes you need to read will be dictated in part by your application. Zarr supports reading subsets of data (with the chunk being the smallest decompressable unit). Ideally, your chunking should align with your access pattern.

-

Decompressing bytes with the Codec Pipeline. Different codecs have different throughput targets, and these can depend heavily on the data, chunk size, and hardware. We’re using the default Zstd codec in this example.

-

Your actual computation. This should ideally be the bottleneck: it’s the whole reason you’re loading all this data after all.

And if you are using a GPU, at some point you need to get the bytes from host to device memory1.

Finally, you might need to store your result. If your computation reduces the data this might be negligible. But if you’re outputting large n-dimensional arrays this can be as or more expensive than the reading.

In this case, we don’t really care about what the computation is; just something that uses the data and takes a bit of time. We’ll do a bunch of matrix multiplications because they’re pretty computationally expensive and they’re well suited to GPUs.

Notably, we won’t do any kind computation that involves data from multiple shards. They’re completely independent in this example, which makes parallelizing at the shard level much simpler.

Example Workload

This workload operates on a 1-D float32 array with the following properties:

| Level | Shape | Size (MB) | Count per parent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chunk | (256_000,) |

1.024 | 400 chunks / shard |

| Shard | (102_400_000,) |

409.6 | 8 shards / array |

| Array | (819_200_000,) |

3,276.8 | - |

Each chunk is Zstd compressed, and the shards take about 77.5 MB on disk giving a compression ratio of about 5.3.

The fact that the array is 1-D isn’t too relevant here: zarr supports n-dimension arrays with chunking along any dimension. It does ensure that one optimization is always available when decoding bytes, because the chunks are always contiguous subsets of the shards. We’ll talk about this in detail in the Decode bytes section.

Our workload will read the data, transfer it to the GPU (if using the GPU) and perform a bunch of matrix multiplications.

Performance Summary

This example workload has been fine-tuned to make the GPU look good, and I’ve done zero tuning / optimization of the CPU implementation. Any comparisons with CPU libraries are essentially bunk, but it’s a natural question so I’ll report them anyway.

The top level summary will compare three implementations:

- zarr-python: Uses vanilla zarr-python for I/O and decoding, and NumPy for the computation.

- zarr-python GPU: Uses zarr-python’s built-in GPU support to return CuPy arrays, so the GPU is used for computation. At the moment, this still uses Numcodecs to decompress the data, which runs on the CPU. After decompression, the data is moved to the GPU for the matrix multiplication.

- Custom GPU: My custom implementation of I/O and decoding with CuPy for the computation.

| Implementation | Duration (ms) |

|---|---|

| Zarr / NumPy | 19,892 |

| Zarr / CuPy | 3,407 |

| Custom / CuPy | 478 |

You can find the code for these in my CUDA Stream Samples repository.

Please don’t take the absolute numbers, or even the relative numbers too seriously. I’ve spent zero time optimizing the Zarr/NumPy and Zarr/CuPy implementations. The important thing to take away here is that we have plenty of room for improvement. My Custom I/O pipeline just gradually removed bottlenecks as they came up, some of which apply to zarr-python’s CPU implementation as well. Follow https://github.com/zarr-developers/zarr-python/issues/2904 if you’re interested in developments.

The remainder of the post will describe, in some detail, what makes the custom implementation so fast.

Performance optimizations

Once you have the basics down (using the right data structures / algorithm, removing the most egregious overheads), speeding up a problem often involves parallelization. And you very often have multiple levels of parallelization available. Picking the right level is absolutely a skill that requires some general knowledge about performance and specific details for your problem.

In this case, we’ll operate at the shard level. This will be the maximum amount of data we need to hold in memory at any point in time (though the problem is small enough that we can operate on all the shards at the same time).

We’ll use a few techniques to get good performance in our pipeline:

- No (large) memory allocations on the critical path.

This applies to both host and device memory allocations. We’ll achieve this by preallocating all the arrays we need to process the shard. Whether or not this should be considered cheating or not is a bit debatable and a bit workload dependent. I’d argue that the most advanced, performance-sensitive workloads will process large amounts of data and so can preallocate a pool of buffers and reuse them across their unit of parallelization (shards in our case).

Regardless, if we’re doing large memory allocations after we’ve started processing a shard (either host or device allocations for the final array or for intermediates) then these allocations can quickly become the bottleneck. Pre-allocation (and reuse across shards) is an important optimization if it’s available.

- Use pinned (page-locked) memory for host buffers

Using pinned memory makes the host to device transfers much faster. More on that later.

- Use CUDA streams to overlap I/O and Computation

Our workload has a regular pattern of “read, transfer, decode, compute” on each shard. Because these exercise different parts of the GPU (transfer uses the memory subsystem, decode and compute launch kernels that run on the GPU’s cores), we can run them concurrently.

We’ll assign a CUDA stream per shard. We’ll be very careful to avoid stream / device synchronizations so that our host program schedules all the work to be done.

Throughout this, we’ll use nvtx to annotate certain ranges of code. This will make reading the Nsight Systems report easier.

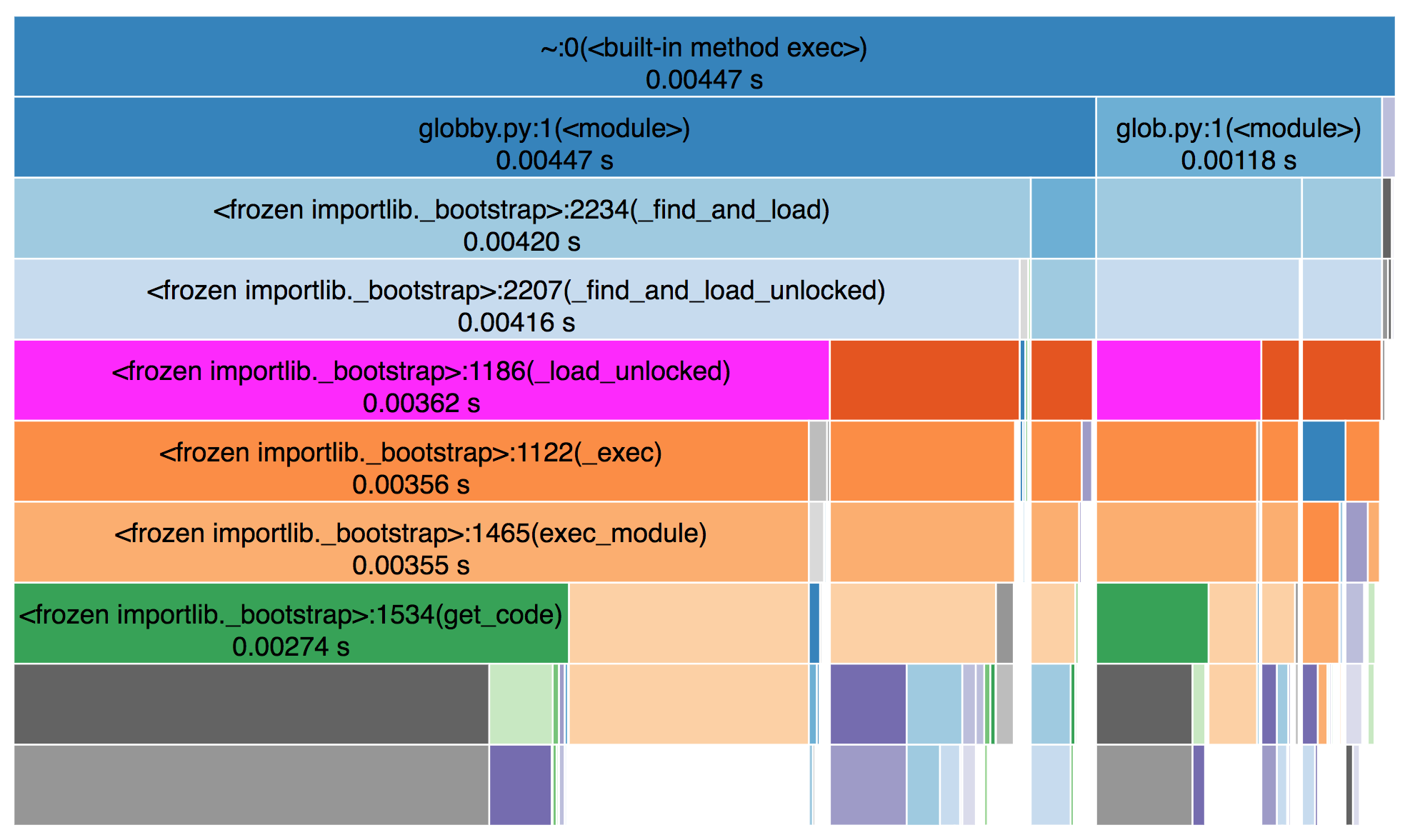

Here’s a screenshot of an nsys profile, with a few important bits highlighted (open the file for a full-sized screenshot):

- Under Processes > Threads > python, you see the traces for our host program,

in this case a Python program. This will include our nvtx annotations

(

read::disk,read::transfer,read::decode, etc.) and calls to the CUDA API (e.g.cudaMemcpyAsync). These calls measure the time spent by the CPU / host program, not the GPU.

- Under Processes > CUDA HW, you’ll see the corresponding traces for GPU operations. This shows CUDA kernels (functions that run on the GPU) in light blue and memory operations (like host to device transfers) in teal.

You can download the full nsight report here and open it locally with NVIDIA Nsight Systems.

This table summarizes roughly where we spend our time on the GPU per shard (very rough, and there’s some variation across shards, especially as we start overlapping operations with CUDA streams).

| Stage | Duration (ms) | Raw Throughput (GB/s) | Effective Throughput (GB/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read | 13.6 | 5.7 | 30.1 |

| Transfer | 1.5 | 51.7 | 273 |

| Decode | 45 | 1.7 | 9.1 |

| Compute | 150 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

Raw throughput measures the actual number of bytes processed per time unit,

which is the compressed size for reading, transferring, and decoding.

“Effective Throughput” uses the uncompressed number of bytes for each stage.

After decompression the actual number of bytes processed equals the uncompressed

bytes, so Compute’s raw throughput is equal to its effective throughput.

Read bytes

First, we need to load the data. In my example, I’m just using files on a local disk, though you could use remote object storage and still perform well. We’ll parallelize things at the shard level (i.e. we’re assuming that the entirety of the shard fits in GPU memory).

path = array.store_path.store.root / array.store_path.path / key

with open(path, "rb") as f, nvtx.annotate("read::disk"):

f.readinto(host_buffer)

On my system, it takes about 13.6 ms to read the 77.5 MB, for a throughput of about 5.7 GB/s from disk (the OS probably had at least some of the pages cached). The effective throughput (uncompressed size over duration) is about 30.1 GB/s. I’ll note that I haven’t spent much effort optimizing this section.

Note that we use readinto to read the data from disk directly into the

pre-allocated host buffer: we don’t want any (large) memory allocations on the

critical path. Also, we’re using pinned memory (AKA page-locked

memory) for the host buffers. This prevents the operating system from paging the

buffers, which lets the GPU directly access that memory when copying it, no

intermediate buffers required.

And it’s worth emphasizing: this I/O is happening on the host Python program, and it is blocking. As we’ll see later, time spent doing stuff in Python is time not spent scheduling work on the GPU. We’ll need to ensure that the GPU is fed sufficient work, so let’s keep our eye on this section.

The profile report for this section is pretty boring:

Note what the GPU is doing right now: nothing! There aren’t any CUDA HW

annotations visible above the initial read::disk. At least for the very first

shard we read, the GPU is necessarily idle. But as we’ll discuss shortly,

subsequent shards are able to overlap disk I/O with CUDA operations.

This screenshot shows the profile for the second shard:

Now the GPU is busy with some other operations (decoding the chunks from the

first shard in this case, which are directly above the read::decode happening

on the host at that time). This is partly why I didn’t bother with parallelizing

the disk I/O: only one thing can be the bottleneck, and right now we’re able to

load data from disk quickly enough.

Transfer bytes

After we’ve read the bytes into memory, we schedule the host to device transfer:

with nvtx.annotate("read::transfer"), stream:

# device_buffer is a pre-allocated cupy.ndarray

device_buffer.set(

host_buffer[:-index_offset].view(device_buffer.dtype), stream=stream

)

This is where our earlier discussion on blocking vs. non-blocking APIs comes

in handy. The device_buffer.set call is not blocking, which is why it

takes only ~60 μs on the host. It only makes the CUDA API call to set up

the transfer and then immediately returns back to the Python program (to

close our context managers and then continue to the next line in our program).

The actual memory copy (which is running on the device) takes about 1.5 ms for a throughput of about 52 GB/s (this is still compressed data, so the effective throughput is even higher). Here’s the same profile I showed earlier, but now you’ll understand the context around what happens on the host (the CUDA API call to do something) and device.

I’ve added the orange lines connecting the fast cudaMemcpyAsync on the host to

the (not quite as fast) Memcpy HtoD (host to device) running on the device.

And if you look closely, you’ll see that just above that Memcpy HtoD in teal,

we’re executing a compute kernel (in light-blue). We’ll get to that in a bit,

but this show that we’re overlapping Host-to-Device transfers with compute

kernels.

Decode bytes

At this point we have (or will have, eventually) the Zstd compressed bytes in GPU memory. You might think that “decompressing a stream of bytes” doesn’t mesh well with “GPUs as massively parallel processors”. And you’d be (partially) right! We can’t really parallelize decoding within a single chunk, but we can decode all the chunks in a shard in parallel. My colleague Akshay has a nice overview of how the GPU can be used to decode many buffers in parallel.

I have no idea how to implement a Zstd decompressor, but fortunately we don’t have to. The nvCOMP library implements a bunch of GPU-accelerated compression and decompression routines, including Zstd. It provides C, C++, and Python APIs. A quick note: this example is using a custom wrapper around nvcomp’s C API. This works around a couple issues with nvcomp’s Python bindings.

- At the moment, accessing an attribute on the decompressed array returned by nvcomp causes a “stream synchronization”. This forces essentially blocks the host program from progressing until the GPU has caught up, which we’d like to avoid. We need to issue compute instructions still, and we’d ideally move on to the next shard!

- We’d like full control over all the memory allocations, including the ability to preallocate the output buffers that the arrays should be decompressed into. This is possible with the C API, but not (yet) the Python API.

My custom wrapper is not at all robust, well designed, etc. It’s just enough to work for this demo. Don’t use it! Use the official Python bindings, and reach out to me or the nvcomp team if you run into any issues. But here’s the basic idea in code:

zstd_codec = ZstdCodec(stream=stream)

# get a list of arrays, each of which is a view into the original device buffer

# `device_buffer` is stream-ordered on `stream`,

# so `device_arrays` are all stream-ordered on `stream`

device_arrays = [

device_buffer[offset : offset + size] for offset, size in index

]

with nvtx.annotate("read::decode"):

zstd_codec.decode_batch(device_arrays, out=out_chunks)

# and now `out` is stream-ordered on `stream`

The zstd_codec.decode_batch call takes about 2.4 ms on my machine. Again

this just schedules the decompression call.

The actual decompression takes about 25-45 ms, for a throughput of about roughly 1.7 GB/s.

Again, we’ve pre-allocated the out ndarray, however this is not always

possible. Zarr allows chunking over arbitrary dimensions, but we’ve assumed

that the chunks are contiguous slices of the output array2. If

your chunks aren’t contiguous slices of the output array, you’ll need to

decode into an intermediate buffer and then perform some memory copies

into the output buffer.

Anyway, all this is to say that decompression isn’t our bottleneck. And this is despite decompression competing for GPU cores with the computation. The newer NVIDIA Blackwell Architecture includes a dedicated Decompression Engine which improves the decompression throughput even more.

And for those curious, a brief experiment without compression is about twice as slow on the GPU as the version with compression, though I didn’t investigate it deeply.

Computation

This example is primarily focused on the data loading portion of a Zarr workload, so the computation is secondary. I just threw in a bunch of matrix multiplications / reductions (which GPUs tend to do quickly).

But while the specific computation is unimportant, there are some characteristics to consider about your computation, it should take some non-negligible amount of time, such it’s worthwhile moving the data from the host to the device for the computation (and moving the result back to the host).

The key thing we care about here is overlapping host to device copies with compute, so that the GPU isn’t sitting around waiting for data. Note how the teal Host to Device Copy is running at the same time as the matrix multiplication from the previous shard:

And at this point, you can start analyzing GPU metrics if you still need to squeeze additional performance out of your pipeline.

But I think that’s enough for now.

Summary

One takeaway here is that GPUs are fast, which, sure. A slightly more interesting takeaway is that GPUs can be extremely fast, but achieving that takes some care.

In this workload my custom pipeline achieved high throughput by

- Being very careful with memory allocations and data movement.

- Using pinned host memory to speed up the one host to device transfer per shard

- Use nvcomp and Zarr shards to parallelize decoding many chunks on the GPU

- Use CUDA streams to express our workloads’ shard-level parallelism, so that we can overlap host I/O, host-to-device copies, kernel launches and kernel execution.

I’m hopeful that we can optimize the codec pipeline and memory handling in zarr-python to close the gap between what it provides and my custom, hand-optimized implementation (0.5s). But doing that in a general purpose library will require even more thought and care than my hacky implementation.

If you’ve made it this far, congrats. Reach out if you have any feedback, either directly or on the Zarr discussions board.

-

NVIDIA does have GPU Direct Storage which offers a way to read directly from storage to the device, bypassing the host (OS and memory system) entirely. I haven’t tried using that yet. ↩︎

-

Explaining that optimization in more detail. We need the chunks to be contiguous in the shard. Consider this shard, with the letters indicating the chunks:

| a a a a | | b b b b | | c c c c | | d d d d |In C-contiguous order, that can be stored as:

| a a a a b b b b c c c c d d d d|i.e. all of the

a’s are together in a contiguous chunk. That means we can tell nvcomp to write its output at this memory address and it’ll work out fine. Likewise forb, just offset by some amount, and so on for the other chunks.However, this chunking is not amenable to this optimization because the chunks aren’t contiguous in the shard:

| a a b b | | a a b b | | c c d d | | c c d d |Maybe someone smarter than me could pull off something with stride tricks. But for now, note that the ability to preallocate the output array might not always be an option.

That’s not necessarily a deal-killer: you’ll just need a temporary buffer for the decompressed output and an extra memcpy per chunk into the output shard. ↩︎

Last weekend I had the chance to sail in the 2025 Corn Coast Regatta. I had such a great time that I had to jot down my thoughts before they fade. This post is mostly for (future) me. We’ll return to our regularly scheduled programming in a future post. I have a post on Zarr performance cooking.

First, some context: in August I attended the Saylorville Yatch Club Sailing School Adult Small Boat class. This is a 3-day course that mixes some time in the classroom learning the theory and jargon (so much jargon!) with a bunch of time on the water. I had a bit of experience from sailing on summer weekends with my family growing up, but I wanted to learn more before going out on my own.

We were thrown in on the deep end, thanks to how breezy Saturday and Sunday. Too breezy for sailors as green as us, as it turns out. At least we got to practice capsize recovery a bunch.

Our instructor, Nick, was great. He’s knowledgeable, passionate about sailing, and invested in our success. If you’re near the area and at all interested in sailing, I’d recommend taking the course (and other clubs offer their own courses).

After the course, Nick was extremely generous. He invited us out for the Wednesday night beer can races the Yatch Club hosts, on his Melges 24. This was quite the step up from the Precision 185 we sailed during the class.

I hadn’t done any racing before and was immediately hooked. During the races, I was mostly just rail meat (“hiking” out on the lifelines to keep the boat from heeling over as we go upwind) and tried to not get in the way. But afterwards Nick was adamant about everyone getting to try the other jobs on the boat. Trimming the spinnaker (a very big sail that’s exclusively used going downwind) was awesome. There aren’t any winches on the Melges 24, so you directly feel the wind powering the boat when you’re flying the spinnaker.

Which brings us to last weekend. Nick was looking for some people to crew during the regatta, and we ended with Nick (driving), me (hiking upwind and flying the spin downwind), and a few other sailing school alumni on the boat. We started early on Saturday, rigging the special black carbon fiber sails Nick uses for regattas.

After a quick captains’ meeting we launched the boat and got ready to sail. Saturday was a series of short-distance buoy races. We ended up getting four races in, and our boat took second in each race to a Viper 640 sailed by a very experienced and talented father / son crew1. A couple of races came down to the wire, and we might have won the third race if I hadn’t messed up our last gybe by grabbing the spinnaker sheet on the wrong side of the block and fouling everything up. Oops.

Sunday was the distance race. We started in about the middle of the lake, sailed a very wet 2 – 2.5 miles upwind (southeast) to the Saylorville Dam, followed by a long 4 – 5 mile downwind leg to the bridge on the north side of the lake, and finished with a ~2 mile leg to the end. The wind really picked up on Sunday, blowing ~15 kts with gusts up to 20–25 kts. As we neared the upwind mark, we had some discussions about whether or not to fly the spinnaker. That’s a lot of wind for a crew as inexperienced as we were (we’d only had one practice and the previous days’ races together). We took our time rounding the mark and eventually decided to set it. Nick took things easy on us, and overall things went well. We about went over twice (probably my fault; I was exhausted by the time we got 1/2 down the course) but our jib trimmer bailed us out both times just like we talked about in our pre-race talk. It sounds like even the Viper went over, so I don’t feel too bad.

Our team had really gelled by the end of the regatta. Crossing the finish line in first place was exhilarating. The official results aren’t posted yet, but we think we got first even after adjusting for the PHRF ratings.

I haven’t yet purchased (another) boat, but the Melges 15 and 19 both look fun (my poor old Honda CRV doesn’t have the towing capacity for a 24, alas). Regardless of what boat I’m on, I’m looking forward to spending more time on the water.

-

After the race we were all chatting about boats we’d sailed up. When I mentioned I’d sailed a Nimble 30 that my dad and grandpa had built, Kim (the father crewing on the Viper) asked where they’d built that. Turns out he had also built one, and had visited my dad and grandpa’s while they were working on it. Small world! ↩︎

You can watch a video version of this talk at https://youtu.be/BFFHXNBj7nA

On Thursday, I presented a talk, GPU Accelerated Cloud-Native Geospatial, at the inaugural Cloud-Native Geospatial Conference (slides here). This post will give an overview of the talk and some background on the prep. But first I wanted to say a bit about the conference itself.

The organizers (Michelle Roby, Jed Sundell, and others from Radiant Earth) did a fantastic job putting on the event. I only have the smallest experience with helping run a conference, but I know it’s a ton of work. They did a great job hosting this first run of conference.

The conference was split into three tracks:

- On-ramp to Cloud-Native Geospatial (organized by Dr. Julia Wagemann from thriveGEO)

- Cloud-Native Geospatial in Practice (organized by Aimee Barciauskas from Development Seed)

- Building Resilient Data

InfrastructureEcosystems (organized by Dr. Brianna Pagán, also from Development Seed)

Each of the track leaders did a great job programming their session. As tends to happen at these multi-track conferences, my only complaint is that there were too many interesting talks to choose from. Fortunately, the sessions were recorded and will be posted online. I spent most of my time bouncing between Cloud-Native Geospatial in Practice and On-ramp to Cloud-native Geospatial, but caught a couple talks from the Building Resilient Data Ecosystems track.

My main goal at the conference was to listen to peoples’ use-cases, with the hope of identifying workloads that might benefit from GPU optimization. If you have a geospatial workload that you want to GPU-optimize, please contact me.

My Talk

I pitched this talk about two months into my tenure at NVIDIA, which is to say about two months into my really using GPUs. In some ways, this made things awkward: here I am, by no means a CUDA expert, in front of a room telling people how they ought to be doing things. On the other hand, it’s a strength. I’m clearly not subject to the curse of expertise when it comes to GPUs, so I can empathize with what ended up being my intended audience: people who are new to GPUs and wondering if and where they can be useful for achieving their goals.

While preparing, I had some high hopes for doing deep-dives on a few geospatial workloads (e.g. Radiometric Terrain Correction for SAR data, pytorch / torchgeo / xbatcher dataloaders and preprocessing). But between the short talk duration, running out of prep time, and my general newness to GPUs, the talk ended up being fairly introductory and high-level. I think that’s OK.

GPUs are Fast

This was a fun little demo of a “quadratic means” example I took from the Pangeo forum. The hope was to get the room excited and impressed at just how fast GPUs can be. In it, we optimized the runtime of the computation from about 3 seconds on the CPU to about 20 ms on the GPU (via a one-line change to use CuPy).

For fun, we optimized it even further to just 4.5 ms by writing a hand-optimized CUDA to use some shared memory tricks and avoid repeated memory accesses.

You can see the full demo at https://github.com/TomAugspurger/gpu-cng-2025. I wish now that I had included more geospatial-focused demos. But the talk was only 15-20 minutes and already packed.

Getting Started with GPU programming

There is a ton of software written for NVIDIA chips. Before joining NVIDIA, I didn’t appreciate just how complex these chips are. NVIDIA, especially via RAPIDS, offers a bunch of relatively easy ways to get started.

This slide from Jacob Tomlinson’s PyData Global talk showcases the various “swim lanes” when it comes to programming NVIDIA chips from Python:

This built nicely off the demo, where we saw two of those swim lanes in action.

The other part lowering the barrier of entry is the cloud. Being programmable, a GPU is just an API call away (assuming you’re already set up on one of the clouds providing GPUs).

The I/O Problem

From there, we took a very high level overview of some geospatial workloads. Each loads some data (which we assumed came from Blob Storage), computed some result, and stored that result. For example, a cloud-free mosaic from some Sentinel-2 imagery:

I’m realizing now that I should have included a vector data example, perhaps loading an Overture Maps geoparquet file and doing a geospatial join.

Anyway, the point was to introduce some high-level concepts that we can use to identify workloads amenable to GPU acceleration. First, we looked at a workloads through time, which differ in how I/O vs. compute intensive they are.

For example, an I/O-bound workload:

Contrast that with a (mostly) CPU-bound workload:

Trying to GPU-accelerate the I/O-bound workload will only bring disappointment: even if you manage to speed up the compute portion, it’s such a small portion of the overall runtime to not make a meaningful difference.

But GPU-accelerating the compute-bound workload, on the other hand, can lead to to a nice speedup:

A few things are worth emphasizing:

- You need to profile your workload to understand where time is being spent.

- You might be able to turn an I/O bound problem into a compute bound problem by optimizing it (choosing a better file format, placing your compute next to the storage, choosing a faster library for I/O, parallelization, etc.)

- I’m implying that “I/O” is just sitting around waiting on the network. In reality, some of I/O will be spent doing “compute” things (like parsing and decompressing bytes.) And those portions of I/O can be GPU accelerated.

- I glossed over the “memory barrier” at this point in the talk, but returned to it later. There are again libraries (like KvikIO) that can help with this.

Pipelining

Some (most?) problems can be broken into smaller units of work and, potentially, parallelized. By breaking the larger problem into smaller pieces, we have the opportunity to optimize the throughput of our workload through pipelining.

Pipelining lets us overlap various parts of the workload that are using different parts of the system. For example I/O, which is mostly exercising the network, can be pipelined with computation, which is mostly exercising the GPU. First, we look at some poor pipelining:

The workload serially reads data, computes the result, and writes the output. This is inefficient: when you’re reading or writing data the GPU is idle (indeed, the CPU is mostly idle too, since it’s waiting for bytes to move over the network). And when you’re computing the result, the CPU (and network) are idle. This manifests as low utilization of the GPU, CPU, and network.

This second image shows good pipelining:

We’ve set up our program to read, compute, and write batches in parallel. We achieve high utilization of the GPU, CPU, and network.

This general concept can apply to CPU-only systems, especially multi-core systems. But the pain of low resource utilization is more pronounced with GPUs, which tend to be more expensive.

Now, this is a massively oversimplified example where the batches of work happen to be nicely sized and the workload doesn’t require an coordination across batches. But, with effort, the technique can be applied to a wide range of problems.

Memory Bandwidth

This section was pressed for time, but I really wanted to at least touch on one of the first things you’ll hit when doing data analysis on the GPU: moving data from host to device memory is relatively slow.

In the talk, I mostly just emphasized the benefits of leaving data on the GPU. The memory hierarchy diagram from the Flash Attention paper gave a nice visual representation of the tradeoff between bandwidth and size the different tiers give (I’d briefly mentioned the SRAM tier during the demo, since our most optimized version used SRAM).

But as I mentioned in the talk, most people won’t be interacting with the memory hierarchy beyond minimizing transfers between the host and device.

Reach Out

As I mentioned earlier my main goal attending the conference was to hear what the missing pieces of the GPU-accelerated geospatial landscape are (and to catch up with the wonderful members of this community). Reach out with any feedback you might have.

]]>I have a new post up at the NVIDIA technical blog on High-Performance Remote IO with NVIDIA KvikIO.1

This is mostly general-purpose advice on getting good performance out of cloud object stores (I guess I can’t get away from them), but has some specifics for people using NVIDIA GPUs.

In the RAPIDS context, NVIDIA KvikIO is notable because

- It automatically chunks large requests into multiple smaller ones and makes those requests concurrently.

- It can read efficiently into host or device memory, especially if GPU Direct Storage is enabled.

- It’s fast.

As part of preparing this, I got to write some C++. Not a fan!

-

Did I mention I work at NVIDIA now? It’s been a bit of a rush and I haven’t had a chance to blog about it. ↩︎

My local Department of Education has a public comment period for some proposed changes to Iowa’s science education standards. If you live in Iowa, I’d encourage you to read the proposal (PDF) and share feedback through the survey. If you, like me, get frustrated with how difficult it is to see what’s changed or link to a specific piece of text, read on.

I’d heard rumblings that there were some controversial changes around evolution and climate change. But rather than just believing what I read in a headline, I decided to do my own research (science in action, right?).

The proposed changes

I might have missed it, but I couldn’t find anywhere with the changes in an easily viewable form. The documents are available as PDFs (2015 standards, 2025 draft). The two PDFs aren’t formatted the same, making it very challenging to visually “diff” the two.

The programmers in the room will know that comparing two pieces of text is a pretty well solved problem. So I present to you, the changes:

The 2015 text is in red. The 2025 text is in green. That link includes just the top-level standards, not the “End of Grade Band Practice Clarification”, “Disciplinary Content Clarification”, or “End of Grade Band Conceptual Frame Clarification”.

The Python script I wrote to generate that diff took an hour or so to write and debug. If the standards had been in a format more accessible than a PDF it would have been minutes of work.

I’m somewhat sympathetic to the view that we should evaluate these new standards on their own terms, and not be biased by the previous language. But a quick glance at most of the changes shows you this is about language, and politics. It’s nice to be able to skim a single webpage to see that they’re just doing a Find and Replace for “evolution” and “climate change”.

Some thoughts

I’m mostly just disappointed. Disappointed in the people pushing this. Disappointed that they’re trying to claim the legitimacy of expertise

The standards were reviewed by a team consisting of elementary and secondary educators, administrators, content specialists, families, representatives from Iowa institutions of higher education and community partners.

and then saying they’re merely advisory

The team serves in an advisory capacity to the department; it does not finalize the first proposed revised draft standards

That’s a key component of pseudoscience: wrapping yourself in the language and of science and claiming expertise.

I’m disappointed that they they’re unwilling or unable to present the information in a easy to understand form.

I’m disappointed that they don’t live up to the documents’s own (well-put!) declaration on the importance of a good science education:

By the end of 12th grade, every student should appreciate the wonders of science and have the knowledge necessary to engage in meaningful discussions about scientific and technological issues that affect society. They must become discerning consumers of scientific and technological information and products in their daily lives.

Students’ science experiences should inspire and equip them for the reality that most careers require some level of scientific or technical expertise. This education is not just for those pursuing STEM fields; it’s essential for all students, regardless of their future education or career paths. Every Iowa student deserves an engaging, relevant, rigorous, and coherent pre-K–12 science education that prepares them for active citizenship, lifelong learning, and successful careers.

The survey includes a few questions about your overall feedback to the standards including, confusingly, a question asking if you agree or disagree that the standards will improve student learning, and then a required question asking you to “identify the reasons you believe that the recommended Iowa Science Standards will improve student learning”. I never took a survey design course, but it sure seems like I put more care into the pandas users surveys than this.

After answering the top-level questions about how great the new standards are, you have the option to provide specific feedback on each standard. Cheers to the people who actually go through each one and form an opinion. Mine focused on the ones that changed. I’ve included my responses below (header links go to the diff). Some extra commentary in the footnotes.

HS-LS2-7

A “Solution” is a solution to a problem. The proposed phrasing is awkward, and implies the need for “a solution to biodiversity”, i.e. that biodiversity is a problem that needs to be solved.

The previous text, “Design, evaluate, and refine a solution for reducing the impacts of human activities on the environment and biodiversity.” was clearer1.

HS-LS4-1

The standard should make it clear that “biological change over time” refers specifically to “biological evolution”. Rephrase as

“Communicate scientific information that common ancestry and biological evolution are supported by multiple lines of empirical evidence.”2

HS-LS4-2

The standard should make clear that “biological change over time” is “evolution”. As Thomas Jefferson probably didn’t say, “The most valuable of all talents is that of never using two words when one will do.”3

HS-ESS2-3

I think there’s a typo somewhere in “cycling of matter magma”. Maybe “matter” was supposed to be replaced by “magma”?

HS-ESS2-4

The proposed standard seems to confuse stocks and flows, by saying that the flow of energy results into changes in climate trends. It’d be clearer to remove “trends”. If I dump 100 GJ of energy into a system, do I change its trend? No, unless you’re saying something about feedback effect and second derivatives (if so, make that clearer and focus on the feedback effects from global warming).

I recommend changing this to “Use a model to describe how variations in the flow of energy into and out of Earth’s systems result in changes in climate trends.”4

HS-ESS2-7

To make the interdependency between earth’s systems and life on earth clearer, I recommend phrasing this as “Construct an argument based on evidence about the simultaneous coevolution of Earth’s systems and life on Earth.”

This also gives our students a chance to learn the jargon they’ll hear, setting themselves up for success in the world.5

HS-ESS3-1

Phrasing this as “climate trends” narrows the standard to rule out abrupt changes in climate that aren’t necessarily part of a longer trend. I recommend phrasing this as “Construct an explanation based on evidence for how the availability of natural resources, occurrence of natural hazards, and changes in climate have influenced human civilizations.”

HS-ESS3-4

The proposed standard is unclear. It’s again using “solution” without stating what is being solved. What impact is being reduced?

Rephrase this as “Evaluate or refine a technological solution that reduces impacts of human activities on natural systems.”

HS-ESS3-5

Replace “climate trends” with “climate change”. We should ensure our students are ready for the language used in the field.

HS-ESS3-6

The standard should make it clear that human activity is the cause of the changes in the earth systems we’re currently experiencing. Rephrase the standard as “Use a computational representation to illustrate the relationships among Earth systems and how those relationships are being modified due to human activity.”

Again, if you’re in Iowa, read the proposals, check the diff, and leave feedback before February 3rd.

-

This “solution” thing came up a couple times. The previous standard was phrased as there’s a problem (typically something like human activity is changing the climate or environment): figure out the solution to the problem. For some reason, because everything America does is great or something, talking about human impacts on the environment is a taboo. And so now we get to “refine a solution for increasing environmental sustainability”. The new language is just sloppy, revealing the sloppy thinking behind it. ↩︎

-

I tried being direct here. ↩︎

-

I tried appealing to emotion and shared history, with the (unfortunately, fake) Jefferson quote. ↩︎

-

More slopping language, coming from trying to tweak the existing standard (without knowing what they’re talking about? Or not caring?) ↩︎

-

I guess evolution isn’t allowed outside the life sciences either. ↩︎

Over at https://github.com/opengeospatial/geoparquet/discussions/251, we’re having a nice discussion about how best to partition geoparquet files for serving over object storage. Thanks to geoparquet’s design, just being an extension of parquet, it immediately benefits from all the wisdom around how best to partition plain parquet datasets. The only additional wrinkle for geoparquet is, unsurprisingly, the geo component.

It’s pretty common for users to read all the features in a small spatial area (a city, say) so optimizing for that use case is a good default. Simplifying a bit, reading small spatial subsets of a larger dataset will be fastest if all the features that are geographically close together are also “close” together in the parquet dataset, and each part of the parquet dataset only contains data that’s physically close together. That gives you the data you want in the fewest number of file reads / HTTP requests, and minimizes the amount of “wasted” reads (data that’s read, only to be immediately discarded because it’s outside your area of interest).

Parquet datasets have two levels of nesting we can use to achieve our goal:

- Parquet files within a dataset

- Row groups within each parquet file

And (simplifying over some details again) we choose the number row groups and files so that stuff fits in memory when we actually read some data, while avoiding too many individual files to deal with.

So, given some table of geometries, we want to repartition (AKA shuffle) the records so that all the ones that are close in space are also close in the table. This process is called “spatial partitioning” or “spatial shuffling”.

Spatial Partitioning

Dewey Dunnington put together a nice post on various ways of doing this spatial partitioning on a real-world dataset using DuckDB. This post will show how something similar can be done with dask-geopandas.

Prep the data

A previous post from Dewy shows how to get the data. Once you’ve downloaded and unzipped the Flatgeobuf file, you can convert it to geoparquet with dask-geopandas.

The focus today is on repartitioning, not converting between file formats, so let’s just quickly convert that Flatgeobuf to geoparquet.

root = pathlib.Path("data")

info = pyogrio.read_info(root / "microsoft-buildings-point.fgb")

split = root / "microsoft-buildings-point-split.parquet"

n_features = info["features"]

CHUNK_SIZE=1_000_000

print(n_features // CHUNK_SIZE + 1)

chunks = dask.array.core.normalize_chunks((CHUNK_SIZE,), shape=(n_features,))

slices = [x[0] for x in dask.array.core.slices_from_chunks(chunks)]

def read_part(rows):

return geopandas.read_file("data/microsoft-buildings-point.fgb", rows=rows)[["geometry"]]

df = dask.dataframe.from_map(read_part, slices)

shutil.rmtree(split, ignore_errors=True)

df.to_parquet(split, compression="zstd")

Spatial Partitioning with dask-geopandas

Now we can do the spatial partitioning with dask-geopandas. The dask-geopandas

user

guide

includes a nice overview of the background and different options available. But

the basic version is to use the spatial_shuffle method, which computes some

good “divisions” of the data and rearranges the table to be sorted by those.

df = dask_geopandas.read_parquet(split)

%time shuffled = df.spatial_shuffle(by="hilbert")

%time shuffled.to_parquet("data/hilbert-16.parquet", compression="zstd")

On my local machine (iMac with a 8 CPU cores (16 hyper-threaded) and 40 GB of RAM), discovering the partitions took about 3min 40s. Rewriting the data to be shuffled took about 3min 25s. Recent versions of Dask include some nice stability and performance improvements, led by the folks at Coiled, which made this run without issue. I ran this locally, but it would be even faster (and scale to much larger datasets) with a cluster of machines and object-storage.

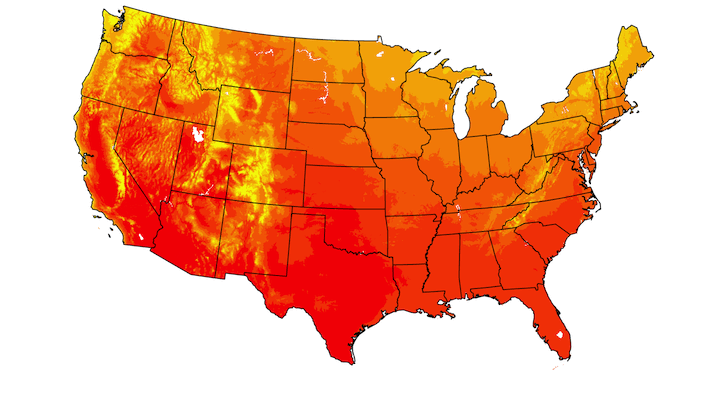

Now that they’re shuffled, we can plot the resulting spatial partitions:

r = dask_geopandas.read_parquet("data/hilbert-16.parquet")

ax = r.spatial_partitions.plot(edgecolor="black", cmap="tab20", alpha=0.25, figsize=(12, 9))

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.set(title="Hilbert partitioning (level=16)")

The outline of the United States is visible, and the spatial partitions do a good (but not perfect) job of making mostly non-overlapping, spatially compact partitions.

which gives

Here’s a similar plot for by="geohash"

And for by="morton"

Each partition ends up with approximately 1,000,000 rows (our original chunk size). Here’s a histogram of the count per partition:

import seaborn as sns

counts = [fragment.count_rows() for fragment in pyarrow.parquet.ParquetDataset("data/hilbert-16.parquet/").fragments]

sns.displot(counts);

The discussion also mentions KD trees as potentially better way of doing the partitioning. I’ll look into that and will follow up if anything comes out of it.

]]>Here’s another Year in Books (I missed last year, but here’s 2022).

Most of these came from recommendations by friends, The Incomparable’s Book Club and (a new source), the “Books in the Box” episodes of Oxide and Friends.

The Soul of a New Machine, by Tracy Kidder

I technically read it in the last few days of 2023, but included here because I liked it so much. This came recommended by the Oxide and Friends podcast’s Books in the Box episode. I didn’t know a ton about the history of computing, but have been picking up an appreciation for it thanks to reading this book. It goes into a ton of detail about what it took Data General to design and release a new machine. Highly recommended to anyone interested in computing.

More Murderbot Diaries

I got caught up on Martha Well’s Murderbot Diaries series, finishing both Fugitive Telemetry and System Collapse. These continue to be so enjoyable. (This Wired piece about Martha Wells and the series is in my reading list).

Nona the Ninth, by Tamsyn Muir

This is third installment in her Locked Tomb series. I don’t remember a ton of details from the plot, but I do recall

- This feeling very different from the previous entries (each of which felt different from their predecessors)

- A general feeling of discomfort and tension, like things could explode at any time, which I think was deliberate

It’s not as simple to describe as “lesbian necromancers in space” like the Gideon the First, but overall, I enjoyed it.

The Cemeteries of Amalo series, by Katherine Addison

These are set in the same universe as The Goblin Emperor, but follow a different main character. I didn’t love these quite as much as The Goblin Emperor (which is just… perfect), but the writing in these is still great. Don’t expect a ton from the plot. These are still more about the world and characters moving through it than anything else.

The Hunt for Red October, by Tom Clancy

This is probably a sign that I’m entering middle age, but yeah this was a fun read. I think I picked this up after Bobby Chesney and Steve Vladek were reminiscing about Clancy novels on the NSL podcast. I didn’t make it through Patriot Games, though, so maybe I still have some youth in me?

Bookshops and Bonedust by Travis Baldree

This is a prequel to Legends & Lattes. If you enjoyed that, you’ll enjoy this one too.

Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

Me and my 8-year old have been working our way through these. We finished The Two Towers earlier in the year and will wrap up Return of the King this week. I’m not sure how much he appreciates all the detailed descriptions of the scenery, but he seems to be mostly following the plot. They continue to be perfect.

A Short History of Nearly Everything by Bill Bryson

I didn’t learn a ton of new actual science from this (humblebrag). If you have a decent high school or liberal arts education you’ll hopefully be familiar with most of the concepts. But I’d recommend reading it regardless because of all the background on the history and people involved in the discoveries (which my courses didn’t cover) and for the great writing. Also, I just love the idea of trying to cover everything in a single, general-audience book.

The Golden Enclaves by Naomi Novik

This is the third in the Scholomance trilogy. The first couple were great. The first especially was very fun, almost pop-corn fantasy (despite a lot of death. Like a lot). But this one somehow is way deeper, and in a way that makes you reevaluate the previous books. It’s maybe less “fun” because of where the story goes, but still great. I read this more recently but it’s stuck with me.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norell by Susanna Clarke

This is a bit hard to review. It does seem to be long (I read it on a Kobo, but wow I see now that Goodreads says 1,006 pages). And while stuff happens, it’s not exactly action packed. Still, I never felt bored reading it, and I was able to follow things clearly the entire time. I think the characters were just so well written that she could bring back a character we haven’t heard from in 400 pages and have us immediately understand who they are and why they’re doing what they’re doing.

Susanna Clarke also wrote Piranesi which I still think about from time to time, and would highly recommend (despite even less happening in that book).

This is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone

This was a reread (I needed something short after the tome that was Jonathan Strange & Mr Norell), but this book had stuck with me since I first read it in 2021. It’s just so, so good. I guess it’s technically a romance set in a Sci-Fi world, which isn’t my usual genera. But I loved it mainly for the writing.

The setting is somewhat interesting, but that’s not really the point: two factions are in a struggle spanning multiple universes (“strands”, in the book). Their agents can travel through time and between strands, and embed themselves in various situations to nudge events along a favorable path. I love a good time-travel book, even if they don’t get into the mechanics.

The characters are somewhat interesting, but they’re also not really the point. We don’t get ton of detail about them (not even their real names; just get “Red” and “Blue”).

And the plot is also somewhat interesting, but I think still not the point. Stuff happens. They write letters to each other. More stuff happens. They fall in love. More stuff happens.

To me, it really comes down to the beautiful writing (with just enough structure around it to make all that flowery prose feel appropriate). I mean… just listen: “I distract myself. I talk of tactics and of methods. I say how I know how I know. I make metaphors to approach the enormous fact of you on slant.”

Overall, I’d recommend this to just about anyone. Plus, it’s short enough that it’s not a huge time commitment if it’s not your cup of tea.

Other

Some honorable, non-book mentions that I’ve started reading this year:

- The Money Stuff newsletter from Matt Levine for money stuff

- The One First newsletter from Steve Steve Vladeck for legal stuff

- Simon Willison’s blog for AI stuff

- Marc Brooker’s blog for distributed computing stuff

Overall, a solid year! My full list is on Goodreads Reach out to me if you have any questions or recommendations.

]]>This post is a bit of a tutorial on serializing and deserializing Python dataclasses. I’ve been hacking on zarr-python-v3 a bit, which uses some dataclasses to represent some metadata objects. Those objects need to be serialized to and deserialized from JSON.

This is a (surprisingly?) challenging area, and there are several excellent libraries out there that you should probably use. My personal favorite is msgspec, but cattrs, pydantic, and pyserde are also options. But hopefully this can be helpful for understanding how those libraries work at a conceptual level (their exact implementations will look very different.) In zarr-python’s case, this didn’t quite warrant needing to bring in a dependency, so we rolled our own.

Like msgspec and cattrs, I like to have serialization logic separate from the core metadata logic. Ideally, you don’t need to pollute your object models with serialization methods, and don’t need to shoehorn your business logic to fit the needs of serialization (too much). And ideally the actual validation is done at the boundaries of your program, where you’re actually converting from the unstructured JSON to your structured models. Internal to your program, you have static type checking to ensure you’re passing around the appropriate types.

This is my first time diving into these topics, so if you spot anything that’s confusing or plain wrong, then let me know.

Overview

At a high level, we want a pair of methods that can serialize some dataclass instance into a format like JSON and deserialize that output back into the original dataclass.

The main challenge during serialization is encountering fields that Python’s json module doesn’t natively support. This might be “complex” objects like Python datetimes or NumPy dtype objects. Or it could be instances of other dataclasses if you have some nested data structure.

When deserializing, there are lots of pitfalls to avoid, but our main goal is to support typed deserialization. Any time we converted a value (like a datetime to a string, or a dataclass to a dict), we’ll need to undo that conversion into the proper type.

Example

To help make things clearer, we’ll work with this example:

@dataclasses.dataclass

class ArrayMetadata:

shape: tuple[int, ...]

timestamp: datetime.datetime # note 1

@dataclasses.dataclass

class EncoderA:

value: int

@dataclasses.dataclass

class EncoderB:

value: int

@dataclasses.dataclass

class Metadata:

version: typing.Literal["3"] # note 2

array_metadata: ArrayMetadata # note 2

encoder: EncoderA | EncoderB # note 4

attributes: dict[str, typing.Any]

name: str | None = None # note 5

Successfully serializing an instance of Metadata requires working through a few things:

- Python datetimes are not natively serializable by Python’s JSON encoder.

versionis aLiteral["3"], in other words"3"is only valid value there. We’d ideally validate that when deserializingMetadata(since we can’t rely on a static linter likemypyto validate JSON data read from a file).Metadata.array_metadatais a nested dataclass. We’ll need to recursively apply any special serialization / deserialization logic to any dataclasses we encounterMetadata.encoderis a union type, betweenEncoderAandEncoderB. We’ll need to ensure that the serialized version has enough information to deserialize this into the correct variant of that Unionnameis anOptional[str]. This is similar to a Union between two concrete types, where one of the types happens to be None.

Serialization

Serialization is relatively easy compared to deserialization. Given an

instance of Metadata, we’ll use dataclasses.asdict to convert the dataclass

to a dictionary of strings to values. The main challenge is telling the JSON

encoder how to serialize each of those values, which might have be “complex”

types (whether they be dataclasses or some builtin type like

datetime.datetime). There are a few ways to do this, but the simplest way to

do it is probably to use the default keyword of json.dumps.

def encode_value(x):

if dataclasses.is_dataclass(x):

return dataclasses.asdict(x)

elif isinstance(x, datetime.datetime):

return x.isoformat()

# other special cases...

return x

If Python encounters a value it doesn’t know how to serialize, it will use your function.

>>> json.dumps({"a": datetime.datetime(2000, 1, 1)}, default=serialize)

'{"a": "2000-01-01T00:00:00"}'

For aesthetic reasons, we’ll use functools.singledispatch to write that:

import dataclasses, datetime, typing, json, functools

@functools.singledispatch

def encode_value(x: typing.Any) -> typing.Any:

if dataclasses.is_dataclass(x):

return dataclasses.asdict(x)

return x

@encode_value.register(datetime.datetime)

@encode_value.register(datetime.date)

def _(x: datetime.date | datetime.datetime) -> str:

return x.isoformat()

@encode_value.register(complex)

def _(x: complex) -> list[float, float]:

return [x.real, x.imag]

# more implementations for additional type...

You’ll build up a list of supported types that your system can serialize.

And define your serializer like so:

def serialize(x):

return json.dumps(x, default=encode_value)

and use it like:

>>> metadata = Metadata(

... version="3",

... array_metadata=ArrayMetadata(shape=(2, 2),

... timestamp=datetime.datetime(2000, 1, 1)),

... encoder=EncoderA(value=1),

... attributes={"foo": "bar"}

... )

>>> serialized = serialize(metadata)

>>> serialized

'{"version": "3", "array_metadata": {"shape": [2, 2], "timestamp": "2000-01-01T00:00:00"}, "encoder": {"value": 1}, "attributes": {"foo": "bar"}, "name": null}'

Deserialization

We’ve done serialization, so we should be about halfway done, right? Ha! Because we’ve signed up for typed deserialization, which will let us faithfully round-trip some objects, we have more work to do.

A plain “roundtrip” like json.loads only gets us part of the way there:

>>> json.loads(serialized)

{'version': '3',

'array_metadata': {'shape': [2, 2], 'timestamp': '2000-01-01T00:00:00'},

'encoder': {'value': 1},

'attributes': {'foo': 'bar'},

'name': None}

We have plain dictionaries instead of instances of our dataclasses and the timestamp is still a string. In short, we need to decode all the values we encoded earlier. To do that, we need the user to give us a bit more information: We need to know the desired dataclass to deserialize into.

def deserialize(into: type[T], data: bytes) -> T:

...

Given some type T (which we’ll assume is a dataclass; we could do some things

with type annotations to actually check that) like Metadata, we’ll build

an instance using the deserialized data (with the properly decoded types!)

Users will call that like

>>> deserialize(into=Metadata, data=deserialized)

Metadata(...)

For a dataclass type like Metadata, we can get the types of all of its

fields at runtime with typing.get_type_hints:

>>> typing.get_type_hints(Metadata)

{'version': typing.Literal['3'],

'array_metadata': __main__.ArrayMetadata,

'encoder': __main__.EncoderA | __main__.EncoderB,

'attributes': dict[str, typing.Any],

'name': str | None}

So we “just” need to write a decode_value function that mirrors our

encode_value function from earlier.

def decode_value(into: type[T], value: Any) -> T:

# the default implementation just calls the constructor, like int(x)

# In practice, you have to deal with a lot more details like

# Any, Literal, etc.

return into(value)

@decode_value.register(datetime.datetime)

@decode_value.register(datetime.date)

def _(into, value):

return into.fromisoformat(value)

@decode_value.register(complex)

def _(into, value):

return into(*value)

# ... additional implementations

Unfortunately, “just” writing that decoder proved to be challenging (have I mentioned that you should be using msgspec for this yet?). Probably the biggest challenge was dealing with Union types. The msgspec docs cover this really well in its Tagged Unions section, but I’ll give a brief overview.

Let’s take a look at the declaration of encoder again:

@dataclasses.dataclass

class EncoderA:

value: int

@dataclasses.dataclass

class EncoderB:

key: str

value: int

class Metadata:

...

encoder: EncoderA | EncoderB

Right now, we serialize that as something like this:

{

"encoder": {

"value": 1

}

}

With that, it’s impossible to choose between EncoderA and EncoderB without

some heuristic like “pick the first one”, or “pick the first one that succeeds”.

There’s just not enough information available to the decoder. The idea of a

“tagged union” is to embed a bit more information in the serialized

representation that lets the decoder know which to pick.

{

"encoder": {

"value": 1,

"type": "EncoderA",

}

}

Now when the decoder looks at the type hints it’ll see EncoderA | EncoderB as

the options, and can pick EncoderA based on the type field in the serialized

object. We have introduced a new complication, though: how do we get type in

there in the first place?

There’s probably multiple ways, but I went with typing.Annotated. It’s not

the most user-friendly, but it lets you put additional metadata on the type

hints, which can be used for whatever you want. We’d require the user to specify